Objectives

At the end of this chapter you should:

know the difference between leather and other skin products such as rawhide, parchment and semi-tanned leather;

understand the adverse effects that moulds, insects, inappropriate environmental conditions and excessive lubrication can have on leather;

know the storage and display conditions which are required to minimise the deterioration of leather objects;

understand the need for careful assessment of leather before attempting any treatment including cleaning;

know some cleaning processes that can be used on leather and be aware of the limitations of each method;

know when to lubricate leather objects; and

be able to prepare and apply lubricants to objects which must remain flexible.

Introduction

Animal skin products have been used since ancient times, and continue to be used. Leather’s durability and workability have made it a very important domestic and commercial product.

Leather has been used in the manufacture of an enormous range of objects, including clothing, saddles, boats, thongs, shields, aprons, shoes, upholstery straps and belts, and covers for books. It has been decorated with gold, dyed, moulded and polished.

While most museums, galleries and libraries in Australia do not have examples of ancient leather, many have leather objects of some kind. It is important that you have the information you need to properly care for the leather objects in your collections.

What is leather?

Leather is one of a range of manufactured materials which can be made from the skin of any animal.

Long before genuine tanning methods were used to prepare leather, hides and skins were processed in a variety of ways. The different processes were all designed to preserve the skins; and each process produced skin products with different properties. Working oil, grease and even brain matter into raw skins, softening hides by chewing them and smoking skins were some of the processes used. These methods affected both the look and feel of skins and their resistance to deterioration.

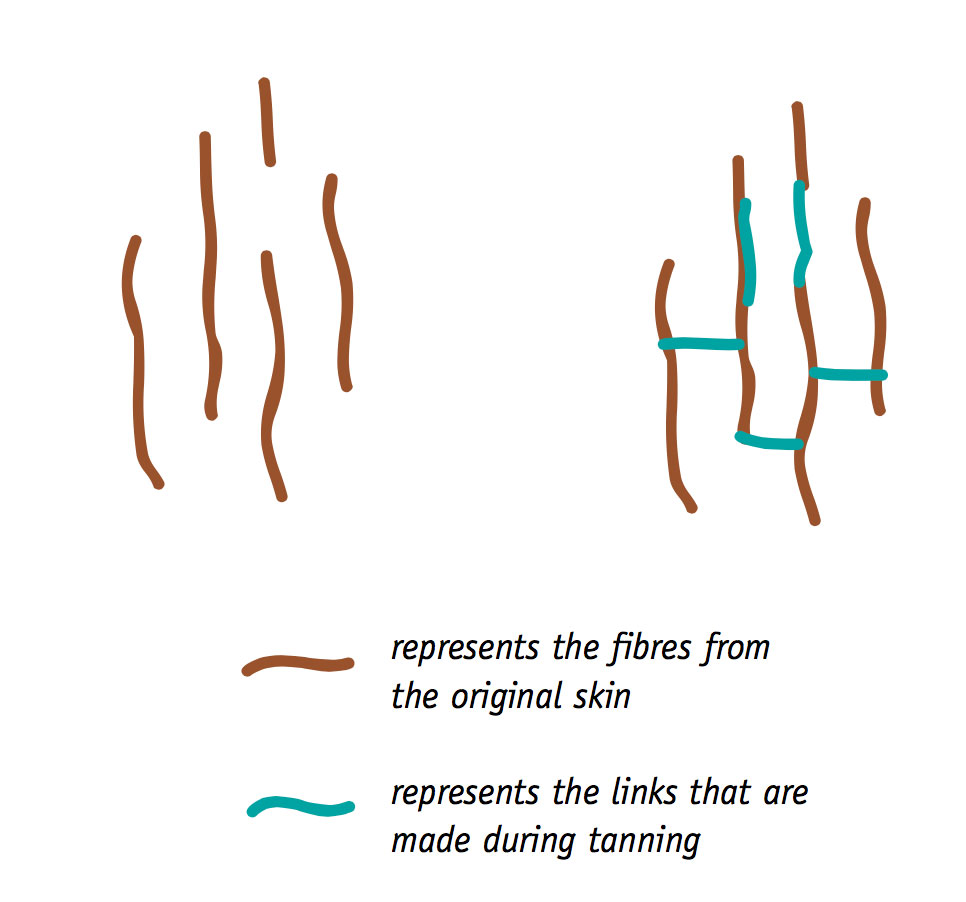

Technically, the term ‘leather' refers to skin products which have been fully tanned. Tanning is a process which chemically alters skins, making them more durable and more resistant to rotting. It does this by chemically linking relatively small molecules and fibres in the original skins into groups of larger molecules and fibres. Large molecules take longer to break down than smaller ones.

Some of the other skin-processing methods also link fibres and result in larger molecules; but none of them do it as fully as the various tanning techniques, and none of them produce a material as durable as leather. Other skin products include rawhide, parchment and vellum, and semi-tanned leather.

Leather is made up of tanned collagen—the protein which makes up skin and bones—moisture, oils and fat.

Leather in good condition is naturally acidic: in the range of pH 3–6, with a water content of between 12–20% and a fat content in the range 2–10%.

What are the most common types of damage?

Leather can be damaged in a number of ways.

It can be scuffed, worn, torn, scratched and abraded—for example, during cleaning—and over- lubricated—this reduces the moisture content of the leather and it will become hard, brittle and inflexible.

Leather is also adversely affected by inappropriate environmental conditions and by biological pests.

Light and UV radiation affect leather in a number of ways, including:

providing energy to the chemical breakdown of the collagen that makes up the leather;

interaction with atmospheric pollutants, producing chemicals that damage leather and other materials associated with it;

fading of dyes; and

skin products with hair still attached often suffer hair loss through light-induced damage.

Extremes of relative humidity are damaging to leather. In low relative humidity conditions, leather dries out and can become hard, brittle and cracked. When the relative humidity is over 65%, leather is susceptible to mould attack. Leather is even more attractive to mould if it has been lubricated too much, because mould uses the ingredients of the lubricants as a food source.

Vegetable-tanned leathers, including items of harness, military equipment and bookbindings and upholstery, are susceptible to deterioration known as red rot, caused by pollutants in the atmosphere.

Dust is a major problem for leather objects because it can cause both chemical and mechanical damage. The sharp edges of minute particles are abrasive, and can cause fibre damage if removed by methods other than suction. Dust also attracts fungal spores, and acts as a centre for condensation and subsequent chemical attack.

Moulds, bacteria, rats, termites and many other insects attack leather and the materials incorporated in it.

Leather is often combined with other materials: metal buckles, for example. The interaction of these materials can be damaging.

Many fatty materials incorporated in leather dressings, react with metal components of leather objects, causing them to corrode. Evidence of this corrosion is often seen, for example, the presence of a turquoise, waxy substance on copper fastenings. Metals may have been incorporated into the leather from materials used during the manufacturing process. Deterioration caused by the presence of metals in the leather is hastened when relative humidity is high.

For more information

For more information about adverse environmental effect, please see Damage and Decay.

Common causes of damage

The most common types of damage are caused by:

poor handling;

poor storage methods;

inappropriate display methods;

wear and tear from repeated use;

chemical changes in the materials which make up the leather objects;

chemical changes caused by atmospheric pollutants and by chemicals which are in contact with the leather objects; and

a combination of any or all of these.

Much of the common damage to leather objects can be prevented by care and pre-planning your handling, storage and display.

Storing and displaying leather

Ideal conditions for storing leather

Ideally, objects made from leather, hide and skin should be displayed and stored in a clean, well ventilated environment where temperature is constant and moderate—in the range 18–22°C. If this cannot be maintained, the maximum temperature should be 25°C.

Relative humidity should be kept in the range of 45–55%. In very dry conditions with the relative humidity below 30%, leather dries out and becomes brittle. High humidity, that is, above 65%, encourages mould growth.

Parchment and vellum are very sensitive to changes in relative humidity, and experience considerable dimensional change as they absorb and release moisture.

Leather must be protected from environmental fluctuations and dust and insect attack. Display cases and layers of storage provide this type of protection.

Lighting levels should be kept to a minimum, particularly for dyed leather. The brightness of light on undyed leather should be 150 lux or less; and on dyed leather it should be 50 lux or less.

A UV content below 30 μW/lm and no higher than 75 μW/lm is preferred for undyed and dyed leather.

Avoid exposing any leather to bright spotlights or direct sunlight, because these can cause leather to fade, discoloured and dry out.

General storage guidelines

Good housekeeping is essential in the care of leather. Vacuum and dust regularly. This helps to minimise mould, insect and rodent attack.

Protect leather objects from dust using Tyvek dust covers, unbuffered acid-free boxes or acid-free tissue.

Check objects regularly to detect mould and insect infestations early.

Leather objects should be fully supported in storage and on display. They should be supported in their desired shape, so that if they harden later there will be no need for reshaping.

Store long leather pieces horizontally to make sure they are supported fully and evenly.

If three-dimensional objects are unable to support their own weight, then they should be supported internally. The form of the support depends on the shape of the object and the weight of leather to be supported. You can support and fill rounded items with unbuffered, acid-free tissue paper, or chemically stable polyethylene or polypropylene foams. You can make supports for other shapes using these foams.

Leather clothing and large objects such as saddles should be fitted on a dummy or a mount made-to- measure. Stable materials, such as the above- mentioned foams, linen, Dacron and most metals can be used in the manufacture of these supports.

Avoid sharp folds or creases in the leather. This helps reduce cracking.

Because leather products are naturally acidic, they should not come into contact with buffered, acid- free materials: these materials are alkaline and potentially damaging to leather.

Storage cupboards and furniture should be made of painted metal—these provide a stable and neutral storage environment for leather objects.

If you have wooden storage and display furniture, it should be sealed and lined with impermeable coatings, for example, clear polyurethane or laminates. This reduces the risk of reactive chemicals from the wood affecting the leather objects or the metal components associated with the objects. Remember, sealants and glues should be fully dry and cured before putting objects into the storage environment.

Standard conservation-quality mounting and framing are usually adequate for the protection of art or documents on parchment.

Treatments

Storing and displaying leather in a well-maintained environment minimises deterioration and the need to treat leather objects. All treatments involve some risk to the object being treated.

Always assess carefully the need for treatment and the type of treatment. If you are in doubt about whether to treat or what treatment to use, ask a conservator for advice.

Use detergents, stain removers and similar chemicals only after talking with a qualified conservator.

Cleaning Leather

Even cleaning has the potential to damage leather. For this reason, cleaning should not be considered as an automatic option for leather objects. Cleaning is recommended for:

objects which need cleaning to prevent deterioration of the leather, which can be caused by surface deposits and/or mould growth; and

recently-acquired objects. Before their addition to the collection, they should be inspected and cleaned if necessary. This is essential to reduce the risk of contaminating the rest of the collection.

Before cleaning leather objects, consider:

the type and condition of the surface to be cleaned;

the nature of any contaminants or dirt;

the type of leather; and

exactly what is to be cleaned.

Dirt or other accretions which have accumulated during an object’s useful life may be seen as historic evidence of the object’s use. You may not want to clean this evidence away.

What to clean

Surface deposits which may need to be removed by cleaning include:

dirt, dust and salts;

fatty spews and gummy spews—materials which migrate to the surface from the lubricants used on leather; and

mould.

To identify crystalline salts, spews and mould you may need to examine the leather surface under magnification:

the crystalline nature of salts would be clearly evident;

mould can be identified by the presence of fine, fibrous strands; and

fatty spews appear greasy, and can be difficult to remove; gummy spews look like resin deposits on the surface of the leather.

Cleaning guidelines

Before cleaning any leather objects, remember to assess the condition of the surface being cleaned. If the object is fragile, cleaning can cause further damage; and it might be better to protect the object from further soiling rather than cleaning it.

It is important to remember that cleaning can stain leather, shift dyes as well as dirt within leather, and remove lubricants from leather. Always make sure that cleaning is necessary before starting.

If cleaning is necessary and the object is able to withstand it, there are a number of techniques you can use.

Vacuum cleaning, with the nozzle just above the leather surface and the power on the lowest setting, is probably the safest cleaning method. It is particularly suited to dusty leather which is in good condition. Place a gauze screen on the end of the nozzle when cleaning. This prevents fragments of leather being lost in the vacuum cleaner. If fragments are being lifted, reduce the suction of the vacuum cleaner.

Brushing with a soft, squirrel hair or camel hair brush is another way of removing surface dirt. Note that even using a soft-bristled brush can damage fragile objects—because dust is abrasive and can scratch a fragile surface. Also, small pieces of damaged leather may be dislodged.

Blowing dirt away with compressed air is appropriate for some objects. Take care that the air stream is not too strong, because it could damage fragile surfaces and dislodge leather fragments. Do this either outside or in a fume cupboard: to prevent dust being redeposited on the object.

Granular erasers can be used to remove more stubborn dirt. Use this method only on surfaces which are in good condition. Remember also that some erasers contain chemicals which can contribute to the deterioration of leather; so it is important that you select your eraser carefully. This is particularly important—it can be difficult to remove all traces of the eraser after cleaning.

To remove thick surface deposits such as those occasionally formed by fatty spews, scrape the surface using a soft, wooden spatula. This method should be used only to remove the bulk of the deposit; and care must be taken not to damage the leather surface. Solvents can be used to remove the remainder of the deposit left after scraping. This method is described below.

Residues or thin films of fatty or gummy spews can be removed using petroleum-based solvents such as white spirit or hexane.

CAUTION:

Before using hexane and white spirit to clean the surface of the leather, test them on an inconspicuous area of the object to check that any surface finish on the leather is not affected by the solvent.

It is necessary to control the application of these solvents, because they can easily spread into the leather and dissolve fats in the body of the skin. The solvents can be applied with a small brush or cotton bud, or a sponge for larger areas. The solvents will soften the fats which you can then remove with a clean, cotton bud or your wooden spatula.

CAUTION:

White spirit and hexane should be used in a well ventilated area. Remember to protect your hands when using these solvents because they will dissolve the oils in your skin, as well as in the leather.

Use a slightly moistened sponge to remove water- soluble dirt from leather objects which are in good condition.

CAUTION:

Use this treatment only where the surface of the object is protected by a water-resistant coating, for example, wax, resin or similar. Water can cause permanent darkening of leather and leave tidemarks in dyed leathers.

Alcohol or alcohol/water mixtures can be used to remove surface salts. Water can stain and damage leather, so keep the water content low. Test the mixture to make sure that it has no effect on the leather surface.

An emulsion cleaner is very effective for removing stubborn dirt. Because this formulation contains some water, test it in an inconspicuous area before applying it on a large scale.

CAUTION:

Do not wet the surface of the leather itself during cleaning. This increases the likelihood of the leather hardening when it dries, and can cause darkening of the leather surface. Use water-based cleaning methods only if the leather surface is water-resistant.

Saddle soap—a note of caution

Anecdotal evidence suggests that, although saddle soap appears to have little detrimental effect on leather objects which are still in use, museum objects which have been cleaned with this soap often seem to be in a worse condition than untreated objects.

CAUTION:

Do not wet the surface of the leather itself during cleaning. This increases the likelihood of the leather hardening when it dries, and can cause darkening of the leather surface. Use water-based cleaning methods only if the leather surface is water-resistant.

Saddle soap—a note of caution

Anecdotal evidence suggests that, although saddle soap appears to have little detrimental effect on leather objects which are still in use, museum objects which have been cleaned with this soap often seem to be in a worse condition than untreated objects.

Of major concern is the alkaline nature of saddle soaps and the effect that the alkalines can have on leather, which is naturally acidic. If saddle soap is the only available cleaning option, it is important to minimise the amount of moisture used. This reduces the penetration of the soap into the leather and minimises the potentially damaging effects of the soap.

Lubrication of leather

Is it necessary?

The usual answer for museum objects is NO!

The main purpose of applying dressings to leather in museums, galleries and libraries is to prevent the leather hardening if the relative humidity fluctuates widely.

If too much lubricant is applied, the leather repels moisture and eventually becomes hard and brittle—the very effects that the application of the dressing was meant to prevent.

Most mould infestation is caused by the presence of too much lubricant.

Some dressings can also darken leather and cause increased stickiness. A sticky surface collects and holds dust, and is very hard to clean.

Lubricants do not provide protection against acidic pollutants.

Consider these points when deciding whether or not to apply a dressing to leather. If the leather is in its required shape, does not need to flex and is in a relatively stable environment, then lubrication is usually not necessary.

As leathers age, their ability to absorb fats and oils effectively is reduced. The amount of fats and oils needed in archaeological and older leathers is less than in their modern counterparts. Lubricating aged leather only causes more problems.

Dressings should not be used to ‘feed’ leather or as a way of improving its appearance. These approaches inevitably lead to over-lubrication and the development of some of the problems outlined above.

If you want to improve the appearance of a leather object which originally had a polished surface, it is better to use a wax polish. Because this is primarily a surface treatment there should be minimal impact on the leather itself.

When should lubricants be used?

Lubricants are really only necessary if:

- flexibility needs to be restored to an object; and

- the leather is displayed in an environment which experiences repeated and extreme fluctuations in relative humidity.

It is important to realise that museum objects rarely need to be flexible, because they are generally not used. They are usually stored and displayed. If the storage environment is stable, there is little need for lubrication.

To restore flexibility to hardened leather, it is necessary to rehumidify or condition the leather before lubrication. Various procedures may be used (Calnan, 1984). These include:

sponging the surface with an alcohol solution diluted with water or a water-based moisturiser;

covering the leather with damp sawdust overnight; and

placing the leather in a humidity chamber.

If an object needs to be reshaped then humidification often will be enough.

The next step in restoring flexibility to leather is the actual lubrication itself.

Types of lubricants for leather

The fats and oils which lubricate the leather can be applied either in a water-based emulsion or dissolved in organic solvents. Fats and oils dissolved in an organic solvent are known as solutions or dressings.

Vegetable oils are not used as frequently as fats, because in the long term they are more prone to oxidation which results in the oil yellowing and hardening; this is followed by loss of the lubricating properties.

A water-based emulsion is best if tests show that:

water does not discolour the surface; and

the surface absorbs water.

Applying oils in emulsion increases the likelihood of oils remaining evenly distributed throughout the interior of the leather. If an emulsion cannot be applied, use a solvent-based dressing.

Guidelines for the use of lubricants

Only apply lubricants to leather which is:

deformed—the lubricant is used to make the object more flexible and to assist in reshaping the object;

extremely dry; or

cracked due to shrinkage.

CAUTION:

Never apply dressings to objects containing untanned or semi-tanned materials such as hides, parchment and vellum.

Always test the lubricant in an inconspicuous area before use.

When the leather is generally in good shape, but is dry and hard, applying a commercial dressing/wax such as Fredelka is useful.

CAUTION:

Fredelka should not be used on items with metal attachments or decorations because it causes corrosion of metal.

If the dryness is only a surface condition, or if the leather is very thin—for example, book covers and car seats—then a preparation such as British Museum Leather Dressing adequately restores surface-oil content.

Apply it sparingly, using a soft cloth. It can be used on leather with metal attachments or decorations. The beeswax in this dressing forms a thin film on the leather surface which can be polished.

Some surface finishes resist the penetration of oils and fats into the leather, whether you use an emulsion or a dressing. If this happens, it is best to rub an oil emulsion into the flesh side—or underside—of the leather, to encourage penetration.

Although many commercial leather dressings are available, these may not be suitable for museum objects because they are designed for leather objects which are being used. Static museum objects have different needs because flexibility is usually not an important consideration.

Do a careful assessment before applying any treatment to the leather of a book cover. In most cases it is preferable to store the books under the best possible conditions.

For more information

For information about applying dressing to leather book bindings, please see the section on Books in Cultural Material.

Treatments of attached metal fittings

The metals most commonly used with leather are iron and copper alloys. The fats present in leather accelerate the corrosion of these metals.

A turquoise-blue, waxy material which forms on copper fittings is usually the most visible sign of corrosion.

Due to the intimate contact between the metals and the leather, immersion in chemical baths is usually not an option for the removal of disfiguring corrosion products.

In some circumstances, treatment chemicals may be applied using bentonite paste.

Most of the copper corrosion products can be removed easily using a soft, wooden spatula. Residues can then be removed using cotton buds soaked in leather emulsion cleaner.

To prevent further corrosion, coat the fittings with microcrystalline or Renaissance wax. A corrosion inhibitor, benzotriazole—5%—may be added to the wax if additional protection is needed.

Iron fittings are best treated using sanding or brushing methods to remove surface rust. Applying microcrystalline wax to the cleaned surfaces protects against further corrosion.

For more information

For more information on using bentonite paste and microcrystalline wax, please see the section on Metals in Cultural Material.

Summary of conditions for storage and display

Summary of conditions for storage and display | ||

Storage | Display | |

Temperature | Reasonably constant and preferably 18–22oC. 25oC is the maximum | Reasonably constant and preferably 18–22oC. 25oC is the maximum |

Relative Humidity | 45–55% | 45–55% |

Brightness of the Light | Dark storage is preferred; | Should be 150 lux or less. If the leather is dyed, the brightness should be 50 lux or less. |

UV Content of Light | Dark storage is preferred but if light | Less than 30μW/lm, no more than 75μW/lm |

Leather in Australia\'s climatic zones

As leather is affected by changes in temperature and relative humidity, different storage and display strategies may have to be adopted for leather objects in each of Australia’s climatic zones. Leather is physically weakened when it is exposed to frequent cycles of expansion and contraction associated with fluctuations in relative humidity. A combination of high relative humidity and pollutants can cause an accumulation of acids and subsequent chemical attack. |

Arid |

This climate is generally very dry, however, in arid areas, it is often very hot during the day and very cold at night. This wide fluctuation in temperature is matched by wide fluctuations in relative humidity, for example from 75%–20% in a day. Leather which is exposed to these conditions is likely to become dry, hard and inflexible. Splitting and cracking are also likely. You can overcome these potential problems by adopting the following practices:

|

Temperate |

A temperate climate is considered a moderate climate, however, temperate climates tend to have a greater range of temperatures than tropical climates and may include extreme climatic variations. Temperate climatic zones are considered to have moderate conditions. It should therefore be easier to maintain conditions reasonably close to those recommended for leather. Care does have to be taken, however, to overcome the extreme climatic variations which still occur in these areas.

|

Tropical |

These climates are characterised by heavy rainfall, high humidity and high temperatures. In tropical zones high temperatures and relative humidities pose the greatest risk to leather objects. To minimise damage to leather objects in these areas the following strategies may be adopted:

|

Skin

Skin is a complex structure made up of:

hair;

sweat glands;

fat;

blood vessels; and

a layer of collagen fibre bundles containing protein. In the corium, or the body of the skin, these fibres are large and losely-woven. In the protective grain layer, these fibres are finely and tightly-packed.

The grain layer or hair side is the outside surface layer of the skin. The underside of the skin is known as the flesh side.

Collagen

Collagen is probably the most abundant protein in the animal kingdom. It is a major component of skin, tendon, cartilage, and is found in bone and teeth.

Collagen molecules are bonded together to produce fibres. In animal skins there is a structure of fibres held together by crosslinks. This structure accounts for the great strength of collagen and the fact that the fibres are insoluble.

These fibres can be broken down to produce a collagen product that has a very random structure—gelatine.

Untanned skin products

Rawhide

Rawhide is the dried skin of an animal which has had all of the flesh removed. It is usually a very rigid, tough material. Despite its inherent toughness rawhide is in many ways the least durable of the skin products.

It is used in the manufacture of suitcases, and for hammer heads, drum coverings, thongs and lashings.

Parchment and vellum

Parchment and vellum are made by stretching the skin on a frame and drying it. The skin is treated with lime to remove fat and hair, and it is washed and scraped repeatedly.

Parchment and vellum are untanned animal skins. Occasionally, tanning solutions are applied to the surface of the parchment or vellum to improve its surface quality.

Parchment and vellum are usually light-coloured, almost opaque, and smooth. They take ink and colours well. Both were widely used as writing materials before the introduction of paper to the West. They have also been used as bookbinding materials. Translucent parchment and vellums were also produced, and sometimes used as window panes.

The terms parchment and vellum are sometimes used interchangeably. Originally vellums came from calf skins—the name vellum comes from the Latin for calf. Vellums tend to be whiter and of better quality than parchments. Modern parchments are generally thought to be inferior to earlier parchments. Many modern parchments tend to be yellowish in colour, a bit greasy and thin. These parchments are often made from split sheepskins.

Never force curled or distorted parchment to open out or to lie flat—this can cause damage. Humidification and drying under tension can restore the parchment but this should only be done by a conservator.

Semi-tanned leather

Semi-tanned leather—buckskin or buff leather—is produced when skin is stretched and an oil and fat emulsion, usually from the brain of an animal, is rubbed into it. The skin is then manipulated until it is dry, soft and flexible. Often it is smoked in the final stage of treatment.

New, semi-tanned leather is soft, suede-like, extremely flexible and durable.

In earlier times, semi-tanned leather was used for clothing, lining, pouches, gloves, saddle seats, and military uniforms and equipment. The most common modern example is chamois or wash leather.

In museums, galleries and libraries, untanned and semi-tanned skin materials must never be allowed to come into contact with water.

Leather

Skins are tanned to make leather in order to:

get rid of smaller molecules which will degrade readily, within the skin;

stop biological degradation—that is, rotting; and

produce a product that is, flexible, strong and resistant to deterioration.

Skins which are to be tanned go through a number of pre-tanning processes. The skins are:

cured—dried quickly to achieve a temporary preservation so that they can be transported without rotting;

soaped—this returns the moisture to the dried skins and removes water-soluble materials;

unhaired—this loosens hair and fats so that they can be scraped and pulled away. This process produces a plump hide;

cleaned and the flesh side levelled. During this stage, hair, dirt, grease and remnants of chemicals from previous processes are removed;

delimed—the unhairing process uses lime which makes the skins very alkaline. This stage of the processing reduces the alkalinity, in preparation for the next treatment stages;

bated—this process makes the skins soft and flexible. It also cleans the fibre network of the skins and removes some of the smaller and weaker fibres. Traditionally, dung was used in this process;

drenched—this is similar to bating, but uses weak organic acids. Traditionally, fermented grains were used; and

pickled—this is the final stage that conditions the skins for tanning.

The next stage in making leather is tanning. The tanning process draws collagen fibres together and creates crosslinks between them. This crosslinking on a molecular and fibre level makes the skin much more resistant to deterioration. Generally, leathers are either vegetable-tanned or mineral-tanned.

Vegetable tanning uses tannins which are present in the barks, woods, leaves and fruits of certain plants. The colour of the leather prior to finishing ranges from pale-brown to a reddish brown, depending on the particular tanning agents used. Vegetable-tanned leathers are particularly suitable for bookbinding.

Mineral processing uses mineral salts to chemically stabilise the skin. In the 1880s, chrome salts were used to make leathers which were hard-wearing, stable and water-resistant. The resilience and open texture of chrome-tanned leathers meant that they could not be embossed. These leathers were unsuitable for some kinds of work, particularly bookbinding.

During investigations into the improved durability of leathers, a number of experiments have been carried out using combined tanning techniques.

Another product which is thought of as a leather is alum-tawed leather. These white leathers were produced using a solution of alum and salt. Leather produced by this process is not a true leather, because it does not have the same chemical stability and resistance to water that fully tanned leather has. Zirconium salts are used to produce a white leather that is washable.

Spews

Fatty spews

Fatty spews are fatty or greasy materials which migrate to the leather surface. The materials which migrate to the surface are either solid fats or products of the acidic breakdown of solid fats.

These fatty materials are often present in lubricants used to soften leather. Neatsfoot oil, unless specified as cold-tested, contains a considerable amount of fatty materials. Leather dressings containing neatsfoot oil are a potential source of these spews.

Gummy spews

Gummy spews arise when oils—particularly fish oils—used to lubricate leather, degrade to their constituent fatty acids. These substances migrate to the surface of the leather, where they appear as gummy or resinous deposits. They are unpleasant to touch and handle.

Additional cleaning methods

Cleaning using a granular eraser

In this method an eraser—Artgum 211, Faber Castell, for example—is finely grated using a household grater. It is best to use a plastic grater, because metal graters may rust or shed small, metal particles which could damage the leather.

You could also use Draft Clean Powder, a granulated eraser which is available from suppliers of conservation materials.

The eraser grains are spread over the leather, then lightly rotated with the palm of the hand or the flat of the fingers until the entire area has been covered. Because skin contains oils, or your hands could be dirty, wear cotton gloves. If the area you are cleaning is very small or particularly fragile, use a small brush to move the granulated eraser over the surface.

Vacuum clean thoroughly after cleaning to make sure that the eraser crumbs are removed. This is particularly important, as conservators are concerned about the long-term effects of eraser residues on the texture, colour, pH and wetability of the surface.

Emulsion cleaner

Dirt which is particularly resistant to cleaning can be removed using an emulsion cleaner. This formulation is based closely on one described in the literature (Fogle, 1985).

To make this cleaner, you need:

• 20ml of non-ionic detergent, for example, Teric N9, Arkopal N090;

• 2g of carboxymethylcellulose—CMC; • 1 litre of distilled water; and

• 2 litres of X-4 solvent, hexane.

Mix the non-ionic detergent, CMC, and distilled water vigorously for several minutes before leaving the mixture to stand overnight. This gives the CMC time to swell.

Add 15 parts of this solution to 100 parts of X-4 solvent and shake it vigorously until a creamy emulsion is formed.

This cleaning solution keeps indefinitely, but should be shaken before use.

Before using the cleaner, test it on an inconspicuous area of the object—to make sure that there is no significant effect on the surface coatings on the leather or on the leather itself.

Rub the cleaner onto the surface with a clean cloth, rotating the cloth as it becomes soiled. If the object is very small or delicate, apply the cleaner with cotton buds or some similar soft material. This solution easily removes both fats, oils and water-soluble dirt.

CAUTION:

Before using hexane and white spirit to clean the surface of the leather, test them on an inconspicuous area of the object to check that any surface finish on the leather is not affected by the solvent.

Humidity chamber

A simple humidity chamber can be made using plastic sheeting. The object to be humidified is placed in a plastic tent with a jar containing 50:50 water and alcohol—methylated spirits or ethanol. The alcohol prevents mould formation in the high relative humidity environment created inside the tent. The tent is then sealed with tape.

In addition to being used to condition leather, the raised humidity can also be used to help reshape the leather. As the leather softens it can be reshaped slowly. The time taken for softening depends primarily on the leather thickness and the presence of surface coatings. The object should be removed from the chamber periodically, and progressively eased into the required shape. It is usually necessary to use padding during this process.

Lubricant formulations

The formulations and application methods described below are those recommended by conservators at the Central Research Laboratory for Art and Science, Holland (Fogle, 1985).

Emulsion lubricant

2g of lanolin

10g of neatsfoot oil

6g of surfactant—Teric N9

100ml of distilled water

Warm the first two ingredients together at about 60°C until they melt. Cool the mixture to 20°C and add the surfactant. Mix thoroughly and rapidly. While stirring continuously, add the distilled water bit by bit. When all the water has been added, pour the mixture into a glass cylinder.

Observe the mixture for 10 minutes in the glass cylinder. If it remains stable and does not separate, it is ready for use. This mixture contains no preservatives and does not keep long. Refrigeration extends the life of the mixture.

Paint the cooled emulsion onto the leather using a soft-bristled brush. Allow the leather to dry between coats, if more than one coat is needed to achieve the desired flexibility.

Lubricant solution

2g of lanolin

8g of neatsfoot oil

100ml of Shellsol T—aromatic-free white spirit.

Dissolve the lanolin and neatsfoot oil in the Shellsol T. Paint the solution on the leather using a soft-bristled brush.

Some commercial neatsfoot oil products contain significant quantities of fatty impurities. These impurities will settle out on the surface of leather after dressing to form fatty spews. To remove these from your own neatsfoot oil, refrigerate it then discard the solid upper layer.

British Museum leather dressing

• 200g of lanolin

• 30ml of cedar oil

• 15g of beeswax

• 300ml of X-4 solvent or hexane

To prepare the dressing, the first three ingredients are mixed together and melted by careful heating. The molten mixture is then poured rapidly into the cold X-4 solvent and allowed to cool with stirring. The dressing should be applied sparingly and rubbed well into the leather with clean swabs. After two days the leather may be polished with a soft cloth.

If you have a problem relating to the storage or display of leather objects, contact a conservator. Conservators can offer advice and practical solutions.

For further reading

British Leather Manufacturers’ Research Association 1957, Hides, Skins and Leather under the Microscope, Griffiths & Sons Ltd, London.

Calnan, C. 1984, ‘The Conservation of Social History and Industrial Leather’, Taken into Care: The Conservation of Social and Industrial History Items, Proceedings of the Joint UKIC/AMSSEE Meeting, United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, London.

Calnan, C., ed. 1991, ‘Conservation of Leather in Transport Collections’, Papers given at a UKIC conference, Restoration 1991, United Kingdom Institute of Conservation, London.

Fogle, Sonja, ed. 1985, Recent Advances in Leather Conservation, The Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Washington D.C.

Raphael, T.J. 1993, ‘The Care of Leather and Skin Products: A Curatorial Guide’, Leather Conservation News, Vol. 9 (1) Materials Conservation Laboratory of the Texas Memorial Museum, Austin, U.S., pp 1–15.

Reed, R. 1972, Ancient Skins, Parchments and Leathers, Seminar Press, London and New York.

Tuck, D.H. 1983, Oils and Lubricants Used on Leather, The Leather Conservation Centre, Northampton, U.K.

Waterer, John W. 1972, A Guide to the Conservation and Restoration of Objects Made Wholly or in Part of Leather, G. Bell & Sons, London.

Self-evaluation quiz

Question 1.

Of the possible cleaning techniques, which is the safest to use on leather objects?

a) Brushing with a soft bristle brush.

b) Swabbing with a slightly moistened sponge.

c) Vacuum cleaning, with the machine set on low power.

d) Gently cleaning using a granular eraser.

Question 2.

Lubrication of leather objects in a museum is only necessary if the leather:

a) is hard and dry;

b) needs protection against changes in relative humidity;

c) surface lacks sheen;

d) needs to be protected against pollutants.

Question 3.

Which of the following statements are true?

a) Tanning softens leather.

b) The term leather only refers to skin products which have been fully tanned.

c) Leather has no fat in it.

d) Tanning is a process that chemically alters skins, making them more durable and more resistant to rotting.

Question 4.

Cleaning of leather objects is recommended:

a) on a regular basis, preferably monthly;

b) for new objects before they are added to the collection, if they could contaminate other objects;

c) if the dirt is disfiguring;

d) before an object is put on display.

Question 5.

Which of the measures listed below will help to minimise mould formation on leather?

a) Avoid over-lubrication.

b) Store in the dark.

c) Maintain good air circulation.

d) Clean regularly.

e) Keep relative humidity below 65%.

Question 6.

The major advantage of water-based emulsion lubricants is that:

a) they promote an even spread of oil through the leather;

b) they do not darken the leather surface;

c) they induce greater flexibility than do solvent-based dressings;

d) they penetrate the leather better than solvent-based dressings.

Question 7.

Which of the following statements about storing leather are correct?

a) Folds and creases should be avoided.

b) Buffered acid-free tissue should be used for support.

c) Long leather pieces should be stored horizontally.

d) Storage cupboards should be made of painted metal.

e) Low light levels are best.

Question 8.

In the long term, over-lubrication of leather can cause:

(i) increased desiccation of the leather;

(ii) formation of fatty spews;

(iii) a leather that is too soft;

(iv) formation of mould under conditions of high RH;

(v) the attraction of dust to a greasy surface.

Which of the above statements are correct?

a) All of them.

b) (i), (ii), (iii) and (iv).

c) (ii), (iii), (iv) and (v).

d) (i), (ii), (iv) and (v).

Answers to self-evaluation quiz

Question 1.

Answer:c).

Question 2.

Answer: b).

Question 3.

Answer: b), d).

Question 4.

Answer: b).

Question 5.

Answer: a), c).

Question 6.

Answer: a).

Question 7.

Answer: a), c), d), e). b) is not correct. Buffered tissue should not be used as it is alkaline, while leather is naturally acidic.

Question 8.

Answer: d).