Objectives

At the end of this chapter you should:

have an understanding of the main factors that contribute to the deterioration of books;

have practical knowledge about how to store and display books so that damage is minimised;

have a basic knowledge and some practical skills so that you can make boxes, and do basic repairs in the best and safest manner, and use appropriate materials to preserve books in your collections;

understand the need for ongoing maintenance and management of books—to ensure access to them—while at the same time minimising the risk of damage; and

have a basic knowledge of book structures and the range of materials which go to make up books.

Introduction to the care and repair of books

Books have been with us for centuries. In early years, they were rare and owned usually by wealthy people or the Church. With the invention of moveable type in 1440, text could be mass- produced. This inevitably led to wider distribution and greater demand for books. But they were not produced immediately on the massive scale with which we are now familiar.

Over time, increased demand for books led to a shift from books being hand-made by craftspeople to a greater mechanisation of production. Mechanisation and the availability of cheaper materials have meant that we can meet the massive demand for books; but books are no longer what they used to be, and we have to deal with the consequences of these changes in book production.

Books, old or new, cheap or valuable, are still treasured. People love books—for the information they hold, as objects, as gifts and as collectors’ items—and it is important that you are able to take steps to care for the books in your collections.

Parts of the book

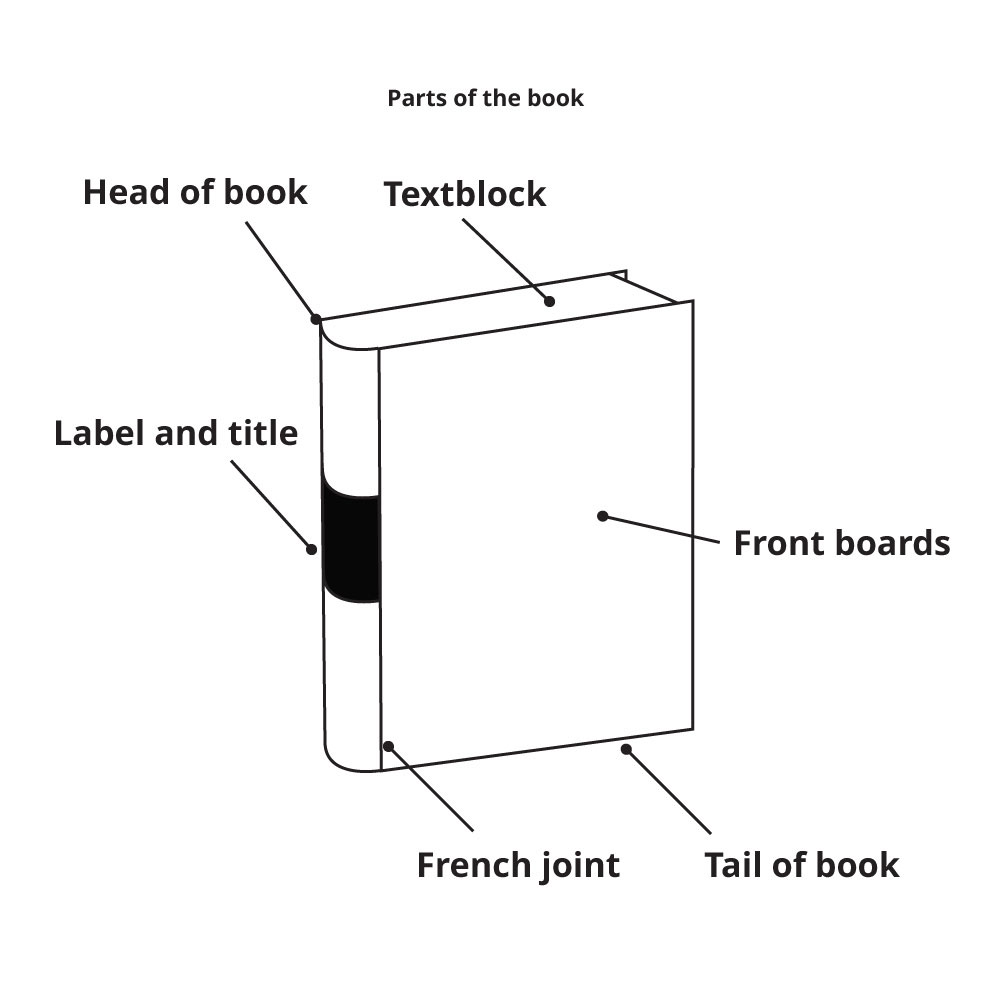

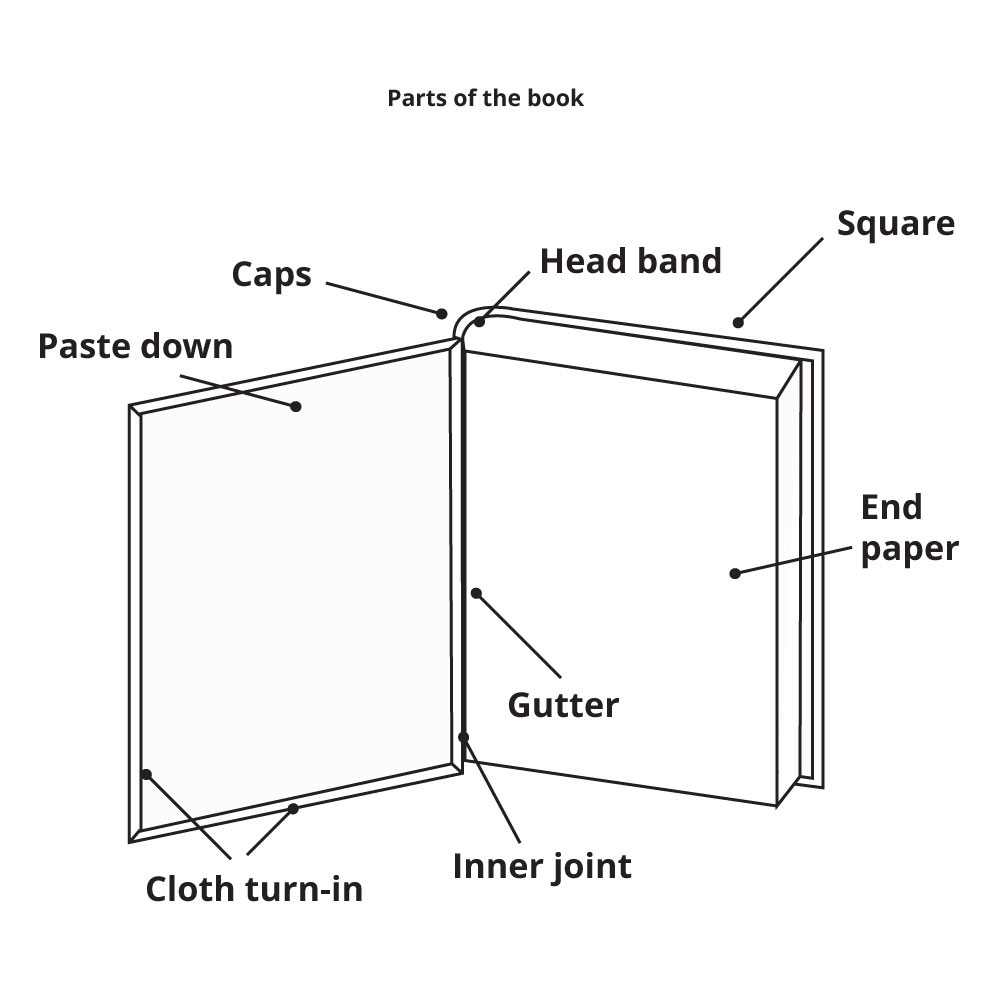

There are a number of unique terms used to describe the parts of a book. It is useful to identify the main parts of books by these terms, because they are used throughout this section.

The following diagrams give a simple overview of the main parts of books.

The textblock is generally made up of:

- sections or gatherings. These are folded sheets of paper grouped together. The individual sections are joined to others by sewing through the folds. This is the traditional, textblock form; and

single sheets of paper glued, sewn or glued and sewn together. This is a modern binding and is more likely to fall apart.

What are the most common types of damage?

Books are vulnerable to physical damage and to the damage caused by chemical deterioration of their components.

Physical damage is very obvious and includes problems such as:

dog-eared pages;

tears to pages;

loss of pages—especially in modern books made up of single sheets attached by sewing or gluing;

broken joints and detached covers;

scuffing, wearing and losses to the bookcloth, leather or paper covers;

insect attack;

wear and tear from excessive or careless use; and

distortions caused by fluctuations and extremes of relative humidity and temperature in storage and display environments.

Damage caused by chemical deterioration includes:

the textblock and binding materials fading, becoming discoloured and becoming brittle. This can be caused by exposure to UV radiation and high lighting levels and the ageing of the materials in the book and the materials with which the book is in contact;

mould growth—mould digests the materials on which it grows; and

damage from pollutants. This is a problem particularly with leather bindings when they came into contact with sulfur dioxide pollution. This produces a condition called red-rot.

For more information

For more information about adverse environmental effects, please see Damage and Decay.

Book structure, materials and damage to books

The life-span of books will be determined to a large degree by:

their structure and their ability to open well in use; and

the materials from which they are made.

It is important, therefore, to have some information about structure and materials so that you can provide appropriate care.

The book as a structure

All books are three-dimensional structures that are required to move. For this reason they should be strong, flexible and durable. Unfortunately this is not always the case. For example, many modern books, particularly text books and reference books, don’t have adequate sewing and binding structures to support the weight of their textblocks. This is made worse when the books are stored upright in shelves. As a result, the textblocks sag and the spines tend to collapse. The sewing also breaks down and the sections within the book begin to come loose.

Some older books bound in the flexible style are very difficult to open fully. The term flexible in this case refers to the spine, which ideally remains flexible and curves when the book is opened allowing the pages to throw open fully. In this style, the covering material, usually leather, is glued tight to the spine of the textblock. Unfortunately, excessive lining and over- enthusiastic use of glue have often led to very inflexible structures. This style of binding is also not suited to textblocks with very stiff paper.

Books are designed to be moving structures, so that they can be opened and read. The evolution of book design did not anticipate the development of flat-bed photocopiers. Many books are being subjected to uses that their structures cannot withstand repeatedly.

CAUTION:

When photocopying a book on a flat-bed photocopier, do not force it open and press it flat to the glass. You may end up with a photocopy— but you could destroy the book in the process.

Deterioration of materials in books

There are a large range of materials used in book production. They are all in very close contact, and will affect each other. If some of these materials are poor quality and begin to deteriorate, they are highly likely to adversely affect the other materials in the book.

Paper is very vulnerable to damage and deterioration if stored in poor conditions, or if made from poor quality ingredients. Many papers, particularly modern papers, become acidic over time. Often the acids develop in the paper from the breakdown of the materials in the paper. These acids attack the cellulose fibres which make up paper, shortening the fibres and making the paper more brittle.

Lignin, from untreated wood pulp, breaks down and produces acids when it is exposed to UV radiation. These acids discolour paper and make it brittle.

Some sizing agents break down to produce acids. Sizes are applied to paper to stop inks soaking into it, as they would into blotting paper.

Chlorine bleaches used to whiten paper can remain chemically active in paper for a considerable time. Chlorine can combine with moisture from the air to produce hydrochloric acid.

Impurities in the water used during papermaking can damage paper. Copper and iron are particularly damaging.

Paper is a food source for insects, rodents and moulds.

Boards on hardcover books, and the thin cardboard covers on paperbacks, are made in a similar way to paper and they often have many of the same problems as paper. They can become acidic and these acids can migrate into the textblock.

Strawboard is an exception. Lime is used in its manufacture, so the board is quite alkaline. It

has a distinctive, brown-yellow colour which when wet readily stains anything it contacts. This stain can often be mistaken for discolouration caused by acids.

The interaction of adhesives, covering materials and boards in conditions where relative humidity fluctuates can cause severe distortion of the boards. This leaves the textblock vulnerable to damage.

Some inks and pigments can damage paper. For example:

iron gall inks—which were used extensively for manuscripts—contain acids and iron, which both attack paper;

verdigris—basic copper acetate—was used in many Islamic books, particularly in borders around text. In many cases, this pigment has eaten into the paper; and the text it surrounded can easily drop out.

Many inks and pigments are affected by UV radiation, high lighting levels and extremes of temperature and relative humidity; this results in inks fading and discolouring, and sometimes becoming blurry.

Animal glue is essentially a poor-quality, impure gelatine. It is a rich food source for insects and moulds—cockroaches enjoy a good munch on animal glue. Animal glue breaks down when it

ages. It often becomes discoloured and darkens, which can cause staining. It can also become very brittle. When this happens, it crumbles and falls away.

Vellum and parchment are untanned animal skins. They are both very moisture-sensitive. In high relative humidity conditions the skins absorb moisture and can distort and cockle. As the relative humidity decreases, the skins dry and become less flexible, and distortions and creases can become set into the skin.

Vellum and parchment can be attacked by insects and mould. Unlike paper—because lime is used in their manufacture—they are not susceptible to attack by acids.

The leathers traditionally used for bookbinding are vegetable tanned leathers and are very susceptible to:

- insect and mould attack

- fading when exposed to light and UV radiation

- drying out and losing their flexibility; and

- red rot. Leathers with red rot have a rusty-red colour, and leave fine deposits of red powder on shelves, tables and hands. When the chemicals in leather start to breakdown, the leather becomes powdery. Sulphur dioxide—a common atmospheric pollutant—combines with moisture from the atmosphere to form sulphuric acid, which breaks down the leather fibres. The leather loses its flexibility, splits and crumbles forming a fine red powder.

Many bookcloths are susceptible to damage from mould and insect attack, and to fading caused by excessive light levels and exposure to UV radiation.

Examine your collection. How many books have faded spines, yet the front and back covers are closer to their original colours because they have been protected by the other books on the shelves? Many bookcloths can also be discoloured and damaged by water.

For more information

For more information about leather, vellum and parchment, please see the section on Leather in Cultural Material. For more information about adverse environmental and chemical factors, please see Damage and Decay.

Wear and tear of books

Apart from the deterioration of the materials which make up books, one of the greatest enemies of books is wear and tear. Wear and tear is an apt name for the deterioration caused by excessive, inappropriate or careless use, as well as for the results of this deterioration.

The fact that there are so many books, and that they are so freely and easily available, means that we tend to take them for granted. We don’t handle them correctly and we don’t care for them properly. If we want them to last we have to change all this.

What contributes to wear and tear? Among other things:

- leaving books open face-down to keep your place. This weakens and can eventually break the book structure;

- folding the corners of pages to mark your place;

- careless photocopying on a flat-bed photocopier, particularly where the print is very close to the spine and the book does not open out well;

- careless shelving of books. Books which are meant to be stored upright on shelves are often seen leaning to one side;

- overcrowded shelves;

- removing books from shelves by pulling strongly at the top of the spine;

- handling books with dirty hands, or eating and drinking while reading;

- pressing flowers in books;

- writing in books;

- dropping books; and

- using staples, pins, metal paper clips and rubber bands on or in books.

- In most cases, the effects of wear and tear are not seen immediately, and so little is done. It is important to know how to store, handle and display books correctly—to minimise the damage which can result from wear and tear.

Common causes of damage

All the most common types of damage are caused by:

- poor handling;

poor storage methods; inappropriate display methods; wear and tear from repeated use; - chemical changes in the materials which make up books; and

- chemical changes caused by chemicals which are present in materials in contact with books, or which are present as pollutants in the atmosphere.

Much of the common damage to books can be prevented by care and pre-planning your handling, storage and display of books.

The following sections will outline practical steps you can take to minimise this type of damage.

The do\'s and don\'ts of handling books

Care and commonsense in handling books will help to prevent damage.

When removing a book from the shelf don’t pull it by the top of the spine because you can cause a great deal of damage this way.

The correct way to take a book from a shelf is to push the books on either side of it further into the shelf and hold the book firmly, with your hand around the spine and your fingers on one cover and your thumb on the other. For this reason, it is wise to leave some space between your books and the back of the shelf when you first set them up on a shelf.

Make sure your hands are clean when you handle books. Otherwise you can leave dirty marks on the bindings and the pages. Wearing gloves provides added protection—cotton gloves are recommended—but they are not always appropriate because they can make it much harder to turn the pages. Clean, close-fitting surgical gloves are a good alternative to cotton gloves. But cotton gloves should be worn when handling books with gold leaf decorations on the covers or on the foredge of the book.

Books should be opened gently: the spine and the sewing can be broken if the book is forced open. If you’re using a book which can’t open flat, give it some support so that you don’t strain its structure. Some book supports are shown in the section on supporting books when they are on display; but you can also improvise—by using another smaller book or, perhaps, the jumper you are carrying with you in case it gets cold.

When opening new or newly bound books, don’t open them from the centre. Start from the front and then the back, and open them gradually, section by section, until you reach the middle. This eases them open gradually and flexes the new structure. Opening them at the middle and forcing them to open flat can break the structure.

It is always best to turn pages slowly and with care. It is very easy to tear paper if you are flicking through the pages quickly. Don’t lick your fingers to turn pages—the moisture can set dirt into the paper. You can also transfer dirt and germs from the paper to your mouth. If the book has been fumigated against insects or mould, you can put yourself at risk.

Don’t try to carry lots of books at once. You could hurt yourself and if you drop the books you will damage them. If you are carrying valuable books, put them in a sturdy box.

The covers of books can be severely disfigured by abrasion and scratching. This is especially noticeable with very smooth, calf-leather bindings. Don’t stack valuable or delicate books, or carry them in such a way that they will rub against each other.

The do\'s and don\'ts of repair labelling

Inappropriate labelling and repair methods can damage and devalue books. The following guidelines may help to prevent such damage.

If books are damaged, be aware that some repairs can cause further damage. For this reason it is recommended that you do not use sticky tapes of any kind.

These tapes go through a number of stages when they deteriorate. Firstly, the adhesive becomes very sticky and will be absorbed easily into paper, bookcloths and leather. In the next stage the adhesive changes chemically, and begins to yellow and eventually turns a dark orange. At this stage, the adhesive is almost totally insoluble and the stains cannot be removed. Once the adhesive becomes insoluble, the tape usually falls away, so the repair has failed and you still have the damage. In addition to the original damages, the paper is now badly stained as well.

Don’t attempt to mend torn pages or damaged covers, unless you have good-quality materials and are confident that the methods you use will not cause damage in the future. Talk to a conservator if you’re not certain that you’re doing the right thing, or if you want information about training courses.

If the boards have come off one of your books, don’t try to reattach them with sticky tape. It is better to place the book, with its cover, in a wrapper or a phase box until it can be repaired properly. The book can still be used, but it is protected properly until it is treated.

Ball-point pens or other ink pens and markers should not be used to label books. Many of these inks, particularly felt tip pen inks, can spread and cause unsightly staining. If you need to handwrite a label, it is best to use a permanent ink—such as Indian ink.

If you use rubber stamps or embossing stamps regularly for labelling your books, be careful about where you place the stamp. Many books have important images and printed plates, and these can be ruined if a stamp is placed over the image or over part of it.

Paper clips, even plastic ones, can damage and distort paper. They should not be used for attaching labels or marking your place. Metal paper clips rust over time and stain paper.

Storing and displaying books

Adverse storage and display conditions affect all items in a collection. The effects are not always dramatically obvious. Changes tend to occur gradually over a long period of time; but once the changes have occurred they are often irreversible, or involve complex and costly treatment.

Good storage and display environments prevent physical damage and help slow down chemical deterioration, greatly increasing the life of books. The following sections outline:

- the ideal conditions for the storage and display of books;

- general storage guidelines;

- the best materials to use for the storage and display of books;

- enclosures for books—some easy do-it-yourself storage enclosures;

- the effects that light can have on books on display;

- lighting hints; and

- supporting books when they are on display.

Ideal conditions for storing and displaying books

Books are made up of many different materials. The sensitivity of particular materials and the value of the books—be it monetary, sentimental or other value—will determine your approach to providing a controlled environment for your collection.

Ideally, books should be stored in an environment where:

Temperature is constant and moderate-in the range 18–22°C. Because books are often stored in areas where people use them, 18°C may be considered too low for comfort. In this case, 20–24°C would be acceptable but higher temperatures than this are not recommended.

Relative humidity is in the range 45–55%. This is important for books. If the relative humidity is too high, mould and insect activity are highly likely to increase because the glues are very attractive to them. If the relative humidity is too low, the glues dry out and lose their flexibility. Because paper, leathers, bookcloths and glues react at different rates to changes in relative humidity—and because fluctuations in relative humidity can cause bindings to distort—it should be kept as stable as possible.

Light is kept to the minimum necessary for the activity. Ideally, books should be stored in the dark. Light is really necessary only when they are being selected from the shelves. This is not always practical because books are often stored in the same area in which they are used; and in libraries, selection of books from shelves can continue over many hours. It is necessary to have light for display, but the lighting levels for display don’t need to be as high as the lighting levels in a reading room.

Books fall into different categories of light- sensitivity, depending on the materials from which they are made, their value and their condition. Most collections of general-use books would be considered to be non-sensitive to light. Despite this, if you want them to last, you should try to keep their exposure to bright light down to a minimum.

All books should be protected from exposure to daylight. The UV content of the light should be less than 30μW/lm and no more than 75μW/lm.

If the books are particularly sensitive to light—for example, books with watercolours, dyed leathers, some older dyed bookcloths and rare or valuable books with paper covers—the brightness of the light should be 50 lux or less.

If the books are moderately sensitive to light, the brightness of the light should be 250 lux or less.

Steps must also be taken to protect books from dust and pollutants—especially if your collection contains leather-bound books.

For more information

For more information about adverse environmental effects, please see Damage and Decay.

General storage guidelines

Careful consideration should be given to the storage site and the storage system. In ideal conditions, a good storage system in an appropriate storage site provides added protection for your collection. If the available facilities or the local climate make it difficult for you to achieve ideal conditions, then the selection of the storage site and the maintenance of a good storage system are even more critical in preventing damage to the collections.

The following notes are guidelines for selecting storage sites, and outline the principles to be followed to protect your collections in storage.

Wherever possible, the storage site should be in a central area of the building, where it is buffered from the extremes of climatic fluctuations which can occur near external walls or in basements and attics. The storage site should not contain any water, drain or steam pipes, particularly at ceiling level. Leaking pipes can cause a lot of damage. Basements should also be avoided because of the risk of flooding.

Don’t store books in sheds. The storage site and the shelving used for your books should allow reasonable ventilation. Also remember to inspect and clean book shelves regularly. These two simple measures help reduce the risk of insect and mould infestation and help greatly in controlling any outbreaks.

Give books adequate support and try to reduce the physical stresses which can damage them. Many books are very badly shelved. This eventually distorts the binding and can damage the sewing structure, which causes books to fall apart. Don’t allow books to flop to the side on their shelves. Bookends or book shoes should be provided to keep books upright. Book shoes also support the textblock.

Store large volumes flat rather than upright. Most large volumes have heavy textblocks, and not all of them have adequate binding structures to support them. Flat storage prevents the weight of the textblock from collapsing the spine. If several heavy books are to be stored horizontally, they should not be stacked too high. This makes handling awkward and can cause damage. Try to place an empty table or shelf nearby—the books on the top of the stack can be put there if you are trying to remove those at the bottom.

Provide easy access to books—ease of access contributes greatly to the care of books. Difficult access often leads to awkward handling as people try to lift too much weight at one time, risking injury to themselves and damaging the books.

The best materials for storage and display of books

Books can be affected by other materials in their immediate environment. The following list of good and bad materials—from a preservation viewpoint—can help you select your storage and display furniture, or the materials to use when making them yourself.

acrylic paints and varnishes

cotton

linen

inorganic pigments

polystyrene

polyester film

ceramic

glass

enamelled metal

BAD

uncured paint

wool

felt

PVA glue

PVC

cellulose nitrate

polyurethanes

protein based glues, for example, animal glue

chipboard, unsealed woods—especially hardwoods—Customwood

Storage enclosures for books

People using books are less hasty and take better care if they see that you are taking steps to protect your books.

Boxes and wrappers provide excellent protection for books. They protect against:

light and UV radiation;

dirt and dust;

disasters; and

people.

Many rare and valuable books are stored in purpose made Clamshell boxes. When these are well made, using archival-quality materials, they are one of the best methods for storing individual books.

They are handmade and relatively expensive. If you wish to buy this type of storage box, contact a conservator about having boxes made up or about learning to make them. Clamshell boxes are complicated to make—in some cases even for those who have made them before—so we have not included instructions.

A number of ready-made archival-quality boxes are suitable for storing books.

If you cannot get a box to fit your book exactly, buy one that is a bit big and pad out the excess space with acid-free tissue, to prevent the book moving about too much. Don’t try and force a book into a box that is too small for it. Alternatively, you can make your own storage enclosures. Instructions for some easy storage boxes and wrappers follow.

Easy do-it-yourself storage enclosures for books

Phase boxes

These boxes are called phase boxes because they are used in libraries in phased conservation programs. When damaged books are identified but cannot be fully treated straight away, they are placed in a phase box for protection—phase 1— until they are programmed for treatment—phase 2.

Phase boxes are usually made from folding box board.

To make a phase box:

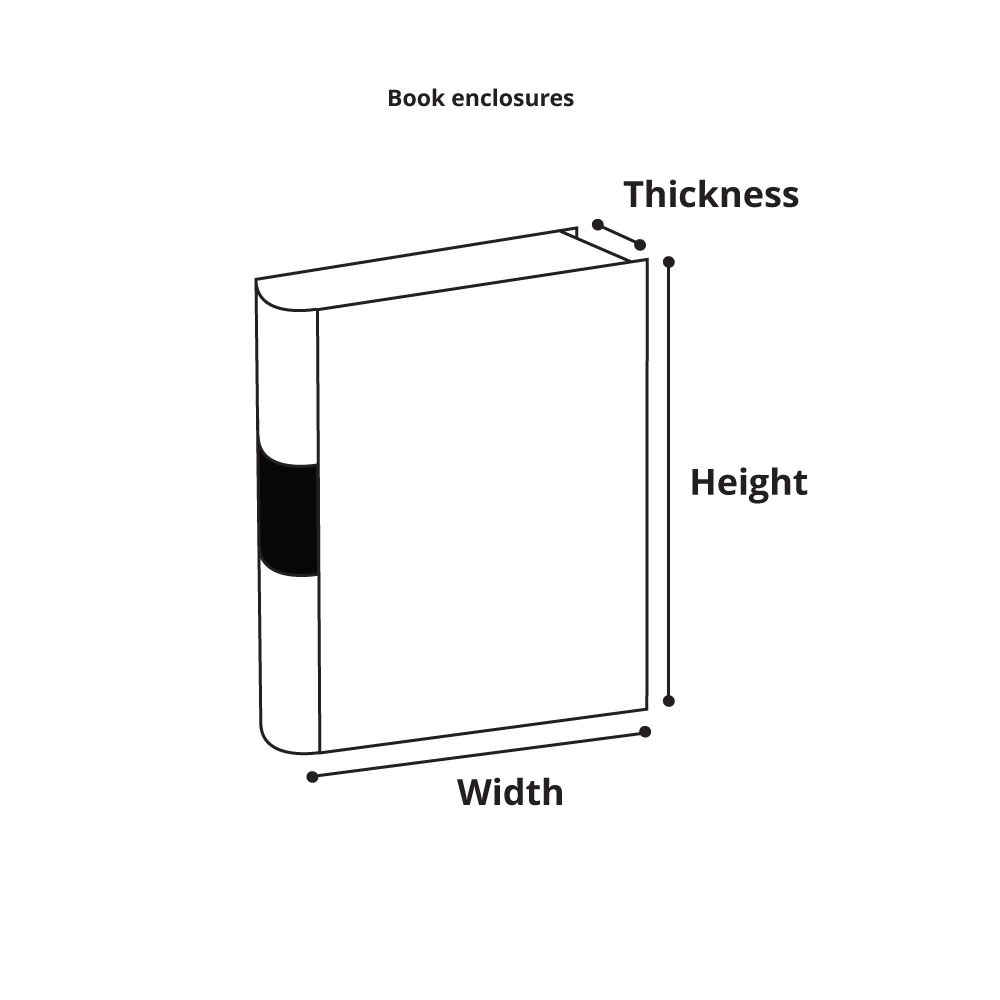

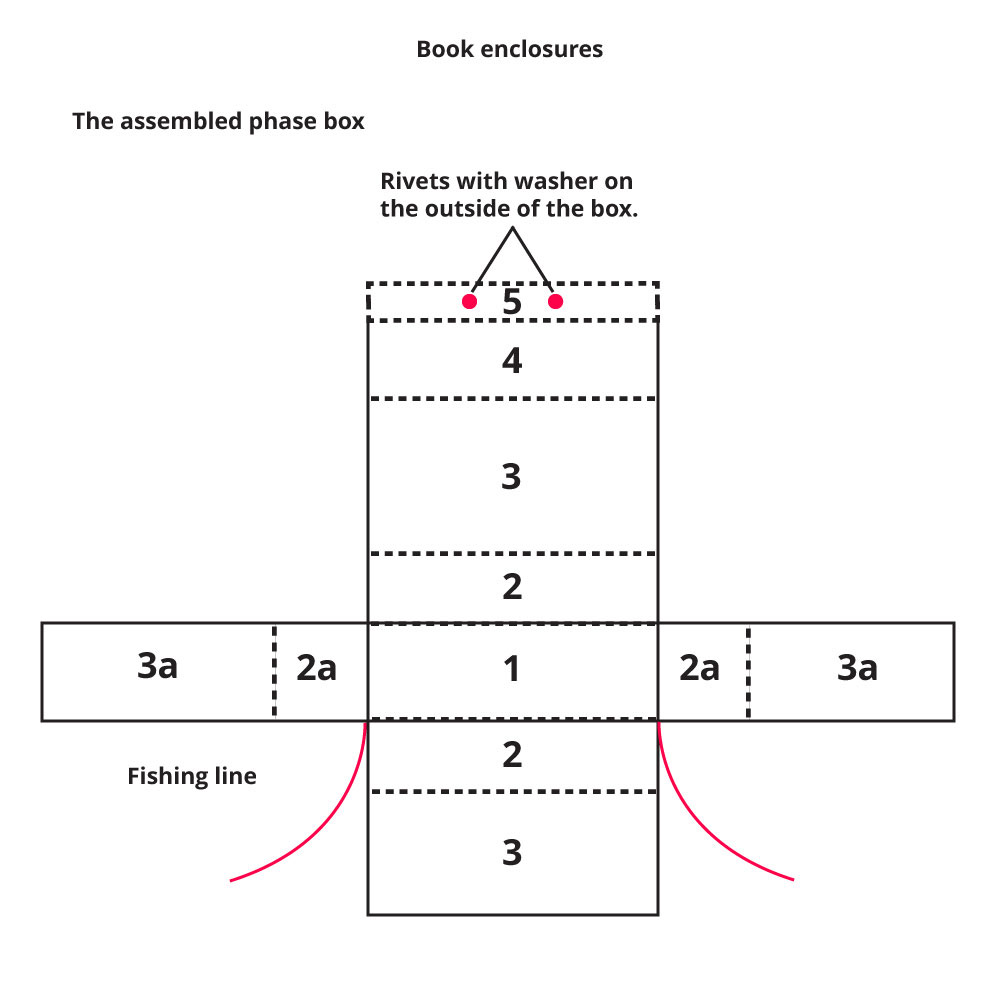

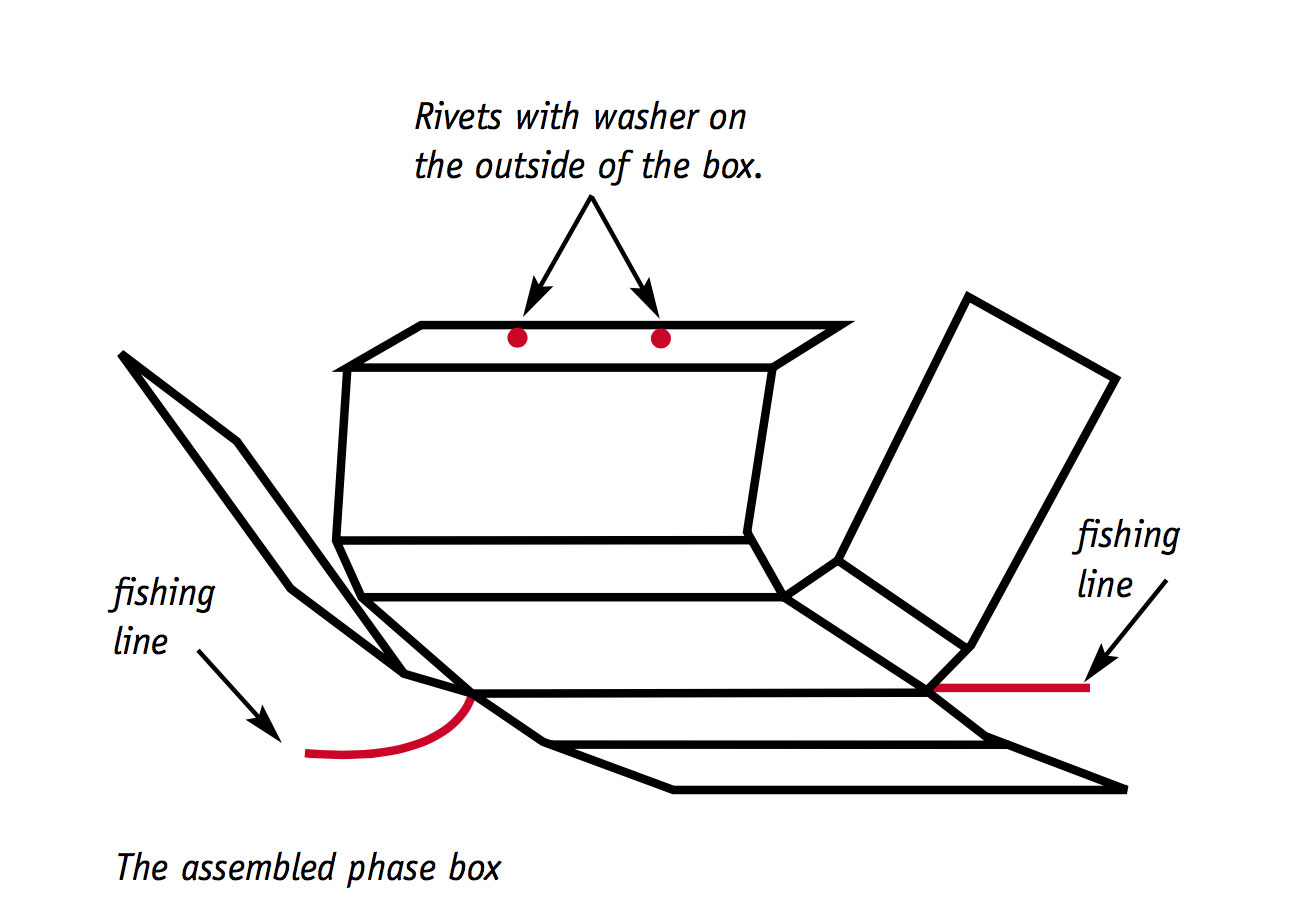

- Measure up two pieces of folding box board. The measurements for these pieces have to relate to the dimensions of the book indicated in the diagram below. The measurements for the first piece should allow for:

- the base, (1) on the diagram below, which is the same as the height and width of the book, with a couple of extra millimetres on each dimension to ensure the fit is not too tight;

- the sides of the box (2) which are the same size as the thickness of the book, plus twice the thickness of the board you are using— this extra allowance is for folding;

- flaps (3) which should be the same size as the base, minus 3mm from the height of the book; and

- an additional flap (4) which is the height of the book and no more than the thickness of the book: this last flap is the place where the rivets and washers for fastening the box are placed.

If the book is very thin—less than 3mm—you need to add an additional flap (5). This flap should be 2–5cm wide.

To cut out the first piece, cut along the solid lines indicated in the diagram.

Fold the board along the dotted lines indicated in the diagram. Because folding box board is quite thick, you may need to score both sides of the board with a bone folder, letter opener or the blunt edge of a knife before folding. Folding box board can have quite sharp corners-you may want to round the corners with a corner rounder, knife or scissors.

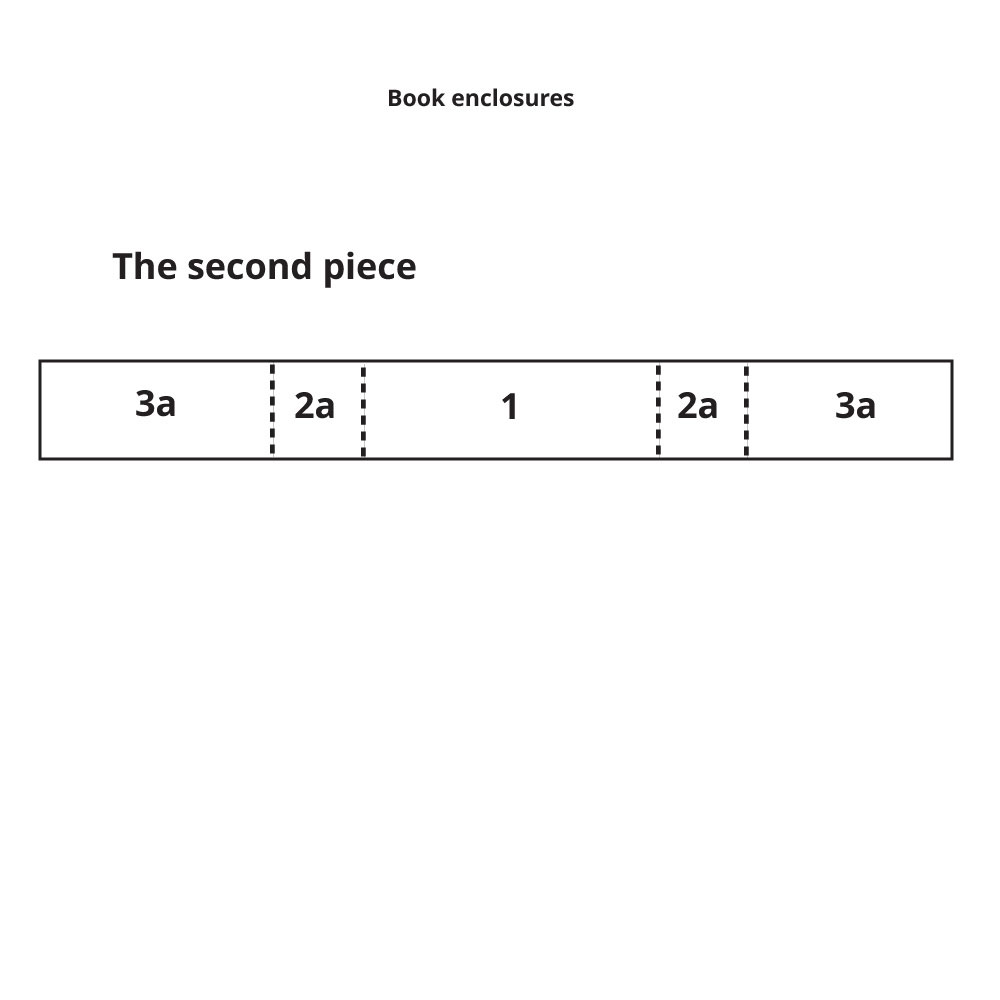

The measurements for the second section should allow for:

the base, (1a) on the diagram below. In this case it is the height of the book plus 2–4mm by the width of the book, plus 2–4mm;

the sides of the box (2a). In this case the sides of the box should measure the same as the sides of the box given for the first piece plus twice the thickness of the board being used. Here you are adding an extra allowance, so that these sides can be slightly larger than the sides on the first piece so they can fold over the flaps of the first piece; and

the flaps (3a) should be the same size as the base except that the width should be the width of the book minus 3mm.

To cut and fold the second piece, follow the procedures outlined for the first section.

To construct the box:

- make two holes in the base of the first section shown on the first diagram by *1*;

- thread some fishing line through this. When the box is folded, the fishing line should be long enough to wrap around the washers that are placed on flap 4 of the first piece;

- stick the first piece to the second piece using a strong adhesive such as polyvinyl acetate— PVA. The base (1) of the first piece should be stuck on top of the base of the second piece (1a), making the second piece of folding box board the outside board;

- allow the adhesive to dry under weights—this prevents the boards warping;

- punch holes in flap 4 of the first piece; and

- cut two circles of folding box board to use as washers. Punch holes in these and using rivets or folding paper fasteners, attach the washers to the outside of the flap.

Now your phase box is complete and you can fold the box, place your book inside the box and fasten it by winding the fishing line around the washers.

A simple book wrapper

Simple wrappers for books can be made from a laminate of good-quality paper and bookcloth. This is prepared by sticking the paper—dampened slightly—to the bookcloth, using a mixture of acid-free PVA and starch paste. The PVA provides an instant stick, while the starch paste gives you a little bit of slip, in case the paper is not positioned correctly on the bookcloth and you need to slide it into position. The laminate should be lightly pressed while drying, and be fully dry before you start to make the wrapper. Drying can take a couple of days. You may need practice in making this laminate, because the paper and bookcloth can be difficult to handle when they are wet with adhesive. Lightweight, archival-quality board is the easier material to use.

CAUTION:

PVA is not used in conservation treatments. It should not be used directly on the book leathers or the textblock, because it is not reversible. As PVA dries, a chemical reaction takes place and the adhesive film which is formed is not soluble in water.

The best tools to use to make the wrapper are a Stanley knife or similar, a metal ruler and a bone folder or letter opener.

To make the wrapper:

mark out the required dimensions on the material-using pencil;

the base of the wrapper should be slightly bigger than the book, to allow it to fold without distorting or damaging the book;

after the base is marked out, you have to mark out the thickness of the book. Again allow a few millimetres more than the actual thickness. The thickness is shown on each flap between the dotted lines;

the side flaps are then marked out. They should be slightly shorter than the base, and tapered from the base to the outside edge;

once it is marked out, the wrapper can be cut. The shaded areas on the diagram are cut away and discarded;

once cutting is complete, the wrapper can be folded. It is easier to fold the board and paper/bookcloth laminate if you run a bone folder, letter opener or the blunt edge of a knife along the fold line first. The dotted lines indicate where the wrapper is folded;

- if you want to make a tab that will fit into a slot in the wrapper to keep the wrapper closed around your book, cut out a tapered tab—shown at the bottom centre of the diagram;

- when the tab has been made, fold up your wrapper and mark out the position and length of the slot. Unfold the wrapper and cut the slot slightly larger than the width of the tab; and

- once cut and folded, the wrapper is ready for use.

How does light affect books on display?

Light is essential in a display environment; but when it is accompanied by UV radiation, it can cause extreme and irreversible damage to many of the materials found in books.

Paper can become brittle and yellow, especially if it contains lignin.

Dyes in bookcloths and leather can fade. This can be seen in books in storage as well. You often see books with faded spines. The spines are exposed to the light, while the covers are protected by being between other books.

If the books are displayed open, then inks, watercolours and photographs in the books can fade or become discoloured.

Lighting hints

As light can be so damaging to books, it is important to consider carefully the lighting of your display. The following hints can minimise damage:

tungsten incandescent bulbs are the best form of lighting for displaying books, because they give out very little UV radiation. If you are using tungsten incandescent bulbs, make sure they are not too close to the books, because the bulbs get very hot and can damage the books. Avoid placing tungsten incandescent bulbs inside display cases because they will raise the temperature inside the cases to unacceptable levels, unless the display cases have air-conditioning or mechanical ventilation;

fluorescent tubes give out UV radiation and should not be used unless you are using low UV-emitting fluorescent tubes; and

it is important that books displayed open have their pages turned regularly: to prevent strain on the binding and excessive light damage to any one page.

For more information

For more information, please see the section on Light and Ultraviolet Radiation in Damage and Decay.

Supporting books when they are on display

Many books need support while being read, and all books should have support when they are on display. Severe damage can result from books being forced to open out flat; and the risks are greater for old, fragile and tight bindings.

There are a number of versatile and effective book supports which are easily and cheaply made.

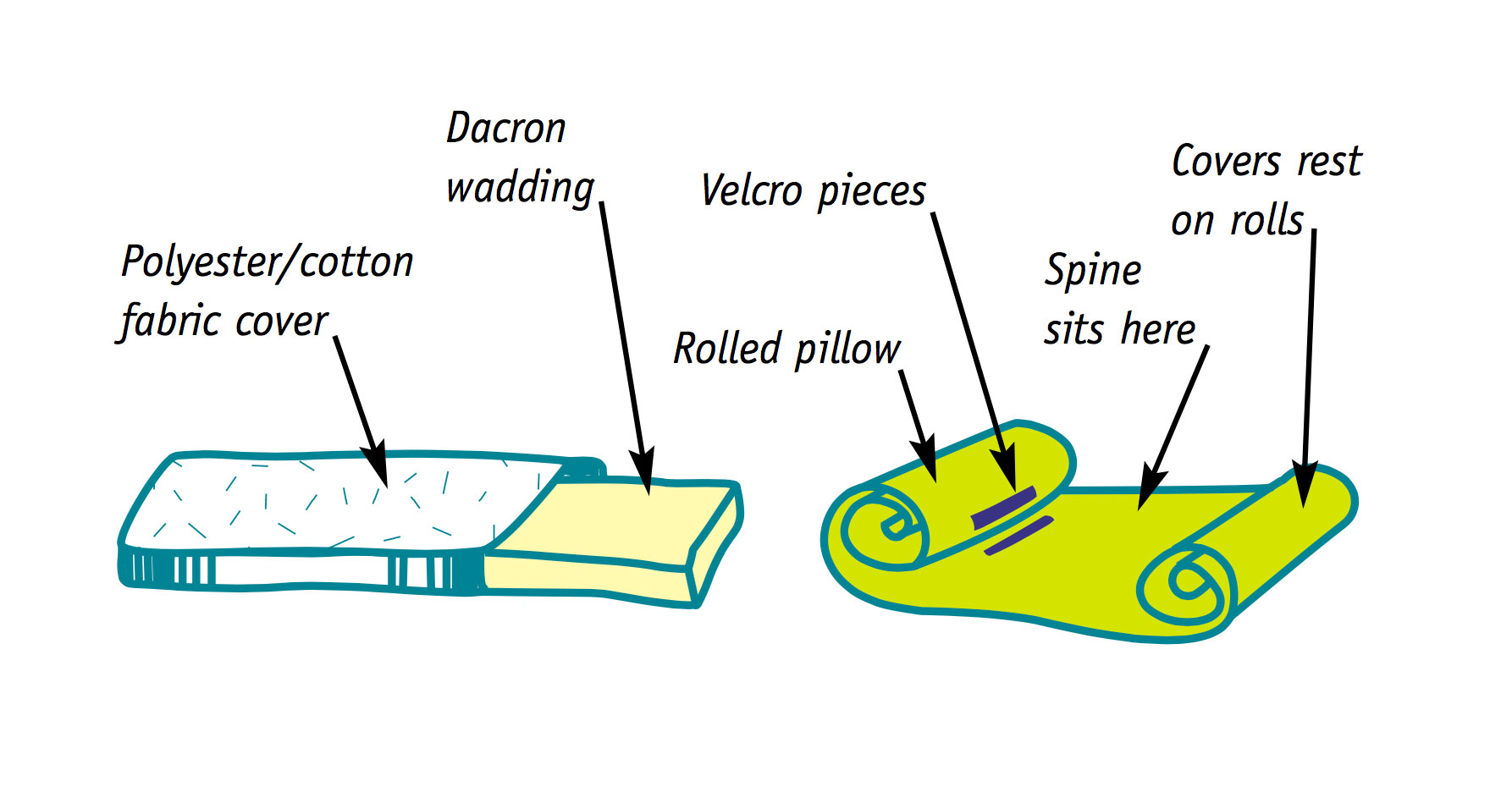

Pillow support or cradle

The materials required for this support are polyester/cotton fabric, Dacron polyester wadding, sewing thread and Velcro.

The support is made first as a flat pillow. The dimensions will be determined by the size and the weight of the book to be supported. For example, an A4-volume can be well supported by a pillow of 1000mm x 350mm.

To turn the pillow into a cradle, the ends are rolled towards the centre—leaving a padded area between the rolls to support the spine of the

book. The width of this central area depends on the width of the book’s spine.

Velcro is stitched to the cradle o fix the two rolled sections in place at the correct angle to support the book for reading and / or display.

Stands for closed books

A simple stand for closed books can be made:

using acid-free mount board for light- to medium-weight books;

by measuring and determining the required dimensions; and

scoring the board where it is to be folded and folding it. The folds, once set at the angle you require, can be set in place by attaching gummed, linen tape to the mount board.

Diagrams reproduced from the Canadian Conservation Institute Note No. 11/8.

A more rigid material, such as Perspex, an acrylic sheet, can be used for larger, heavier books. The acrylic can be bent to the required shape. Most acrylic sheet suppliers can do this if you supply them with the dimensions you require and, if possible, a diagram of what you want.

Supports for open books

When displaying books open at the title page, or first or last sections of the text, support should be provided for the cover. This reduces the compression on the spine, and minimises the risk of damage to the book.

A suitable support can be constructed from acid- free mount board, folded and reinforced as described for the closed-book stand. Again the dimensions are determined by the dimensions of the book: care must be taken to make the spine strip of the book support narrower than the spine of the book.

Diagrams reproduced from the Canadian Conservation Institute Note No. 11/8.

With some books, there will be a tendency for the leaves of the book to open and stand up. This can be prevented by placing a narrow strip of Mylar around the textblock. The Mylar can be joined end- to-end using a small piece of double-sided tape. The tape must not touch the book. It should be placed between the two ends of the Mylar.

A different type of support is needed if the book is quite thick and is to be opened in the middle or if the book is tightly bound and will not open well. Again, this support can be made from acid-free mount board or acrylic sheeting. It presents the book in a V-shaped cavity in which the book rests open at an angle of about 100°—rather than flat at 180°.

Display cases

With some books, there will be a tendency for the leaves of the book to open and stand up. This can be prevented by placing a narrow strip of Mylar around the textblock. The Mylar can be joined end- to-end using a small piece of double-sided tape. The tape must not touch the book. It should be placed between the two ends of the Mylar.

A different type of support is needed if the book is quite thick and is to be opened in the middle or if the book is tightly bound and will not open well. Again, this support can be made from acid-free mount board or acrylic sheeting. It presents the book in a V-shaped cavity in which the book rests open at an angle of about 100°—rather than flat at 180°.

Books are often displayed in cases. Remember, while display cases are a useful method of protecting objects from the harmful effects of the environment and secure from theft and vandalism, books will still need to be supported in a case.

If you are considering using a display case, think about the materials from which it is made. Placing valuable items in cases made from materials that are potentially harmful locks them into a harmful microclimate.

Polishing the top of the display can cause electricity to build up which can make book pages fly open—or snap together. You can prevent this happening by:

- securing the pages with Mylar strips as described in the section Supports for open books; and

- ensuring there is sufficient space between the top of the book and the top of the display case—250mm is a good distance.

Books should not be displayed vertically with their covers open, because the weight of the paper in the textblock will cause distortion. The binding structure may even collapse.

Summary of conditions for storage and display

Summary of conditions for storage and display | ||

Storage Display | ||

Temperature | 18–22oC | 18–22oC |

Relative Humidity | 45–55%RH | 45–55%RH |

Brightness of the Light | Dark storage is preferred for books; but if light is present it should be less than 250 lux. If you think the books are particularly light-sensitive,the brightness should be less than 50 lux. | Should be less than 250 lux. If you think the books are particularly light-sensitive, the brightness should be less than 50 lux. |

Higher lighting levels are necessary when books are being read. The brightness should not exceed 500 lux with exposure to these lighting levels kept to a minimum. | ||

UV Content of Light | Dark storage is preferred; but if light is present, UV content should be less than 30μW/lm and no higher than 75μW/lm. | Less than 30μW/lm and no greater than 75μW/lm. |

Books in Australia\'s climatic zones

The climatic zones outlined below are broad categories. Conditions may vary within these categories, depending, among other things, on the state of repair of your building and whether the building is air conditioned.

Arid |

This climate is generally very dry, however, in arid areas, it is often very hot during the day and very cold at night. This wide fluctuation in temperature is matched by wide fluctuations in relative humidity, for example from 75%–20%RH in a day. When caring for books in arid areas it is important to note that:

|

Temperate |

A temperate climate is considered a moderate climate, however, temperate climates tend to have a greater range of temperatures than tropical climates and may include extreme climatic variations.

|

Tropical |

These climates are characterised by heavy rainfall, high humidity and high temperatures. When caring for collections in high humidity conditions it is important to note that:

|

Book maintenance

Cleaning book shelves thoroughly and regularly helps control insects and mould growth. It is strongly recommended that you set up a system for cleaning your bookshelves regularly. This should involve removing books from shelves and cleaning behind them—insects, such as silverfish, prefer dark, undisturbed places. If you don’t do this regularly, you may not notice an insect or mould problem until there is extensive damage.

Other maintenance procedures that are commonly carried out on books include cleaning individual books and dressing leather bindings. These activities are very important to keep your books in good condition; however, if they are not done properly they can cause damage.

The following sections contain information to assist you with cleaning books and dressing leather bindings.

Handy hints on cleaning books

Books are not always easy to clean. In some cases it is not wise to try to clean them thoroughly, especially if they are in fragile condition. If this is the case, you must approach cleaning with care. If you are not sure whether you should clean a damaged book, consult a conservator.

When cleaning a book, place it on a desk on a clean sheet of paper. By moving the paper around, you can reach all sides of the book easily. This method is easier and safer then trying to hold the book at the same time as you are holding the cleaning tools.

If the book is not fragile and can be cleaned without risk of damage, dust and remove loose dirt from books using gentle brushing combined with suction using a vacuum cleaner. It is vital that you reduce the suction of the vacuum cleaner. You do this by covering the end with one or more layers of a gauze-like material such as fine, Nylon stocking. By reducing the suction you reduce the risk of damage; and the filtering gauze will prevent the loss—into the bowels of the vacuum cleaner— of any loose material which may get picked up by the suction. Sucking dirt away stops it being re- deposited in the book.

You can use a duster on the binding, but extreme care must be exercised. Rubbing with a dustcloth can cause scratching; soft calf-leather is particularly vulnerable. Dusting can also dislodge pieces of degraded leather, cloth or paper. When dusting, remember to keep turning to a clean area of the dustcloth—so as not to re-deposit dirt on the book. Remember also that if you dust without using a vacuum cleaner some of the dust will resettle onto your books.

Brushes can be used for cleaning the outside of books, and for brushing away dirt and dust which have collected inside the textblock. Soft brushes should be used: shaving brushes, sable paint brushes and jewellers and watchmakers’ brushes are particularly suitable.

CAUTION:

Some manuals recommend cleaning the bindings with damp cloths. If you attempt to do this, be very careful because you can damage the binding.

Degraded leathers absorb water easily,

and can remain permanently discoloured where they have been damp.

Some of the sizes and pigments in bookcloths move easily in water, and wiping over with a damp cloth can leave unsightly watermarks on the binding.

Experience and knowledge of the materials are important, as is controlling the amount of water applied and the evenness of the application.

Excess water applied to the outside of a binding can distort the boards, so that they no longer protect the textblock.

Paper can be cleaned using erasers. Be very careful when doing this—and be aware that not all dirt will be moved by an eraser.

The pressure applied must be kept to a minimum, because the paper fibres on the surface of the paper are always disturbed by such cleaning. You can see this damage clearly under a microscope or a thread counter.

CAUTION:

If it doesn’t clean up with slight pressure, STOP—don’t rub harder and harder because you’ll end up with a tear or a hole in the paper.

To clean paper with an eraser, make sure it is well supported and then rub in one direction only. Rubbing back and forth increases the risk of buckling, creasing and/or tearing the paper.

You should pay particular attention to removing the eraser particles from the paper, but some particles will inevitably remain. The brush and vacuum method of cleaning described above is very good for removing eraser particles.

CAUTION:

Do not use strong suction or you could cause extreme damage and distort the pages. Remember to reduce the suction with layers of gauze.

The eraser’s quality is also important. Many modern erasers are made from polyvinyl chloride—PVC. This breaks down in the presence of moisture and produces hydrochloric acid which can cause considerable damage. The eraser should be soft and not contain abrasive materials. Staedtler Rasoplast 526 erasers are used widely for cleaning paper.

Leather dressing—a word of caution

Because leather dries out and becomes inflexible, dressing it is a widespread practice. Good-quality leather dressings improve the function and flexibility of leather, while brightening its appearance. But there are problems associated with using leather dressing.

Excessive leather dressing can stain paper, because it is very greasy. So it is important that you don’t use too much and that you don’t allow it to touch the paper.

Leather dressing can darken degraded leather and should not be applied to cracked or dry leather. These areas should be consolidated first.

Leather dressing can make the surface of the leather sticky, and cause dirt and dust to stick to the leather. This can be avoided by applying the dressing very sparingly and making sure you remove excess dressing by polishing—in much the same way as you do for shoes.

When applying leather dressing, put the dressing onto a soft cloth—such as an old T-shirt—and spread the dressing gently onto the book. Be gentle when polishing away the excess; again use an old T-shirt or similar. If there is any grit in the way, you could easily scratch the leather.

If leather dressing is applied over dirt and dust, they will set in place. Make sure your books are clean before applying dressing.

Leather dressing can get caught in damaged and cracked leather.

Leather dressing can discolour as it ages.

For more information

For more information on leather dressings, please see the page on Leather in Cultural Material.

Some miscellaneous advice

Dust jackets

Dust jackets serve a dual purpose: they protect the surface of the binding materials, but they are often far more decorative than modern bindings. They are often the first part of the book to become damaged.

Some dust jackets are important to the value of the book, and so should be protected.

If you have a valued dust jacket you want to protect, you may decide to remove it and store it safely when the book is being used. If you do this, you may want to put a substitute jacket on your book.

You may prefer to cover the dust jacket while it is on the book. If you do this, choose stable material. Polypropylene is soft enough to fold around the cover and is transparent. Mylar would be more difficult to use and has sharp corners when folded. Secure the overlaps of the covering material with double-sided tape; but don’t allow sticky tapes to be in direct contact with your book or dust jacket.

It is strongly recommended that you avoid using any self-adhesive covering materials.

The adhesive used on these covering materials can work its way into the printed surface of the dust jacket, making the covering material almost impossible to remove later.

Uncut pages

Sometimes you come across a book in which the pages are still joined and the book cannot be read.

If the book is valuable or is a collector’s item, it may be wise to consult a book valuer before going ahead and cutting the pages; in some cases the uncut paper can increase the value of the book.

Don’t cut the pages yourself unless you feel confident that you can do the job without damaging the paper. It is very easy to end up with uneven cuts and jagged edges.

To cut the pages, it is necessary to place a very sharp knife-blade between the pages and slice carefully along the fold. You may need to use a scalpel to get right into the spine, if you are cutting at the head of the book.

If you are not confident about attempting this yourself, ask a conservator for advice or assistance.

Book conservators and bookbinders

Book conservators and bookbinders have a different approach to the treatment of damaged books. Both approaches have their place, but you may want to consider some of these differences before deciding who to consult.

Book conservators following their code of ethics should:

aim for minimum intervention in treatments;

use stable and reversible materials;

retain all original materials. Even if they cannot put all of them back in place they should keep them and return them to you. This way you have all the historic evidence from the book;

document the structure and materials in the book, as well as the damage, before commencing the treatment; and

avoid changing the structure unless the structure itself is causing damage.

Many bookbinders work in a similar way to conservators, but you will also find that some bookbinders:

use unstable adhesives such as animal glue, and irreversible adhesives such as PVA;

proceed with the job without documentation;

discard original materials and at times will not attempt to re-use them;

alter the structure; and

trim the head, tail and foredge after resewing a book. This gives a very even edge, but inevitably makes the textblock smaller.

Think about what sort of job you want and why you are having the work done—it should help you to decide who to go to for your book repairs.

More About Books: A brief history of books

The basic form of the book with which we are familiar today has changed very little over centuries. The book remains a gathering of leaves—most commonly of paper—collected together in some way or another, in a three- dimensional, moving structure, with boards front and back to protect the leaves.

While the basic form has varied little, the materials used, the structural elements and the decorations have varied greatly over the centuries and from country to country. The invention of printing and the subsequent explosion in book production have led to further changes and developments.

Place an early book next to a modern paperback. It is obvious immediately that they are very different in appearance and appeal. But the basic form is the same.

From very early times, multiple leaves of documents were collected together in the form of a roll, with the leaves sewn together end to end. This method was used to attach pieces of papyrus together. The roll form survives today, and can be seen in synagogues: the Scrolls of the Law are written on sheets of parchment sewn edge to edge to form a long roll wound onto two wooden battens called Trees of Life.

As vellum was used more widely, its greater flexibility compared to papyrus gave rise to different methods of collecting the individual leaves together. Vellum could be folded—and so the practice of gathering groups of folded sheets and sewing them onto cords or thongs was developed. They were often wrapped in leather for protection.

Once this form of book gained wide usage, bookbinding was invented. The need to protect the leaves of the books and to keep the vellum sheets flat led to the addition of boards. The cords or thongs to which the groups of folded sheets were sewn were then laced into wooden boards. Gradually this developed into the system for binding books which is still used today.

Over the centuries boards have been covered with leather, parchment, vellum, alum tawed or whittawed skin, papers, and more recently, bookcloth. Boards have also been decorated with blind tooling, gold tooling, jewels, various metals, embroidery, beading, inlaid wood and leather, paste papers and marbled papers.

Decorative elements have not been restricted to the boards. The head, tail and foredge of the textblock can be painted, decorated with Armenian bole—a blood-red pigment—with gold leaf, spatter-painted with colours or gauffered. Headbands are decorative as well as functional.

At various times, different countries developed very individual styles of binding and decoration. Experts can identify the production dates and country of origin for many historic books, based solely on their physical attributes.

Over the centuries, the materials and methods of book production changed. However this has not always meant an improvement in quality. The changes are a reflection of the shift from books as rare items available only to certain sections of society to books as mass-produced consumer goods.

Boards made from compressed paper pulp have replaced wooden boards. Case bindings—in which the cover is made separately from the textblock and attached later—have largely replaced the other forms of binding in which the cover is assembled on the book step-by-step.

In the past, all books were individually hand-sewn. This type of work is generally used today for fine bindings only or conservation work. In modern book production, those books which are sewn are machine-sewn. But huge numbers of books are not sewn: they are made up of individual leaves fastened to each other and to the cover by an adhesive. This style of book—familiar to us as the paperback—is a development of the so-called perfect binding introduced in the 19th century. They are far from perfect—with a tendency to fall apart. There are other books, which have been stapled or, as bookbinders say, wire stitched.

Paper quality has deteriorated also. Acidic paper is an ongoing problem, particularly for libraries. Increasing demand for paper products in the 19th century led to many innovations in the papermaking industry, including a shift away from the traditional materials. The use of pulped wood, alum rosin sizing and papermakers’ alum, to improve the flow of pulp through the papermaking machines, all contributed to the supply of reasonably cheap, mass-produced papers. These materials are also sources of acids, which attack the paper fibres—making the paper brittle and easily damaged when handled.

There is a wealth of knowledge of the history of bookbinding, and centuries of information about the durability of particular materials. This is important for historians, book collectors, museums, galleries and libraries. But this information is also valuable for book conservators, who can use it to great advantage in the preservation of old and new books alike.

Types of bindings

There are many different types of bindings. Brief descriptions of some of the more common types and some of their distinctive features follow.

Flexible style or tight-back. This was the most common binding style until the end of the 18th century, and is still used for fine binding. The term flexible refers to the spine, which ideally remains flexible and becomes concave when the book is opened: allowing the pages to throw open fully. In this style the covering material, usually leather, is glued tightly to the spine of the textblock. So it is sometimes also called a tight-back binding.

Library style. The library style was developed as a sturdy and durable binding which could withstand heavy use. From the middle of the 19th century in Britain, heavy demand for books to supply libraries led to many compromises in production of materials and binding techniques. At the time the look of the binding was more important than its durability. The fact that many of these bindings deteriorated led to the development of the library style. Some features of this style include the following:

the textblock is sewn on linen tapes, rather than the less durable hemp cords;

split boards. The boards are attached to the textblock by inserting the tapes into a split in the board; and

the French joint. This has a space between the spine of the book and the beginning of the front and backboards, which makes it easier to open the book. The endpapers are reinforced with linen.

Paperback. The term paperback really refers to the paper cover. Editions of books are either paperback or hardback. However, many people associate paperbacks with a particular style—one in which the textblock is made of single sheets held together by adhesive applied to the spine. This structure is not very durable. If you look at your book collection you will see that some modern books with paper covers are made up of folded sections sewn together. These are more durable than the adhesive style of paperback, but the covers don’t really offer a lot of protection to the textblock.

Case binding. Many binders don’t consider this a true binding. It was developed as a cheap and relatively easy method of providing protection to the textblock. The case—boards usually covered in cloth—is prepared separately. The textblock and case are attached by pasting the endpapers and spine linings of the textblock to the inside of the case. Many of the classic, decorated, cloth-covered books, especially children’s books from the first part of this century, are case bound. Case binding can be done by machine.

Limp vellum bindings. These bindings have been used for centuries. Their chief characteristic is that they don’t have rigid boards. The textblock is sewn and then covered with a protective covering. This covering is often laced to the sewing cords or thongs. The style is popular as a conservation binding because it is not necessary to use adhesives. It is used with vellum as well as with paper.

Hollow back. The hollow is a spine lining which allows very free opening of books. The hollow lining is a paper tube attached to the spine of the textblock. The covering material is applied over the hollow. When the book opens, the covering material remains curved and supported by one half of the tube, while the textblock becomes concave and is supported by the other half of the tube.

Full binding. This name indicates that the book is covered entirely with the same material, for example, full leather, full cloth.

Half binding. Books that are half-bound have the spine with an overlap onto the boards, and the corners or foredge of the boards, covered in one material, while the remainder of the boards are covered in another. This was an economy measure as the second material was usually a cheaper one. However, it has been used to good decorative effect in many cases.

Quarter binding is another economy measure which is used decoratively. Books which are quarter bound have the spine with an overlap onto the boards, covered in one material, while the boards are covered in another.

Materials commonly found in books

Many materials have been used in book production over the centuries.

Paper is essentially a felted sheet of cellulose fibres. During manufacture, a range of other substances are added to produce papers with infinite differences in quality, use, strength, texture, colour and surface. Paper is an enormously versatile and durable material: we have books dating back centuries which are still in good condition.

Board is a general term covering early wooden boards through to modern, machine-made boards such as pasteboard, millboard, strawboard and others.

Parchment and vellum are untanned animal skins. Their use continued in Europe even after paper was introduced. These materials are rarely found in contemporary books, but were used widely in early manuscript books. Vellum and parchment are manufactured by stretching the animal skins and treating them with lime, while scraping them to remove fats and hair.

Leathers are tanned animal skins. The tanning process gives a degree of chemical stability to the skin. Traditionally, leathers used for binding books were vegetable-tanned. This produced flexible leather with properties excellently suited for binding and decorating books.

Cloth is used in books in a number of ways:

mull is an open-weave, cotton material stiffened with size. It is most often used as a first lining on the spines of textblocks;

Jaconette or Holland cloth, a closely woven cotton or linen, is also used for linings and for strengthening folds of book sections; and

bookcloths are made of closely woven fabrics with pigment fillers and sizes, and sometimes with paper linings to prevent the penetration of glue. Bookcloths can be embossed to create surface textures, and some are coated to prevent scuffing and soiling.

Thread, cords and tape are made from linen. Linen tapes are made from woven, unbleached linen, which is stiffened with size. Cords are made from hemp fibres, spun and combined to make different thicknesses.

Various adhesives are used in bookbinding. They include:

animal glue, which has been used for centuries. It is basically boiled-down animal skins, hooves and bones. It is used hot, and in most binderies the glue pot was kept cooking all day. Prolonged heating causes it to alter chemically and darken. Animal glue is essentially a poor-quality, impure gelatine;

polyvinyl acetate—PVA—is an emulsion adhesive which has been used widely in recent years. It is unsuitable for most conservation applications because it is very difficult to reverse;

starch paste is the favoured adhesive for paper repair; and

glair, which is basically egg white, is used to fix gold leaf to the foredge and to the covers, for example, in the case of gold tooling.

Books can contain a range of inks and other media—iron gall inks, carbon inks, printing inks and watercolours.

These notes on materials are very brief, but serve to illustrate the variety of materials used in books. When used in books, these materials are in very close contact and will inevitably affect each other.

Paper repair

Don’t try to mend torn pages or damaged covers, unless you have good-quality materials and are confident that the methods you use will not cause damage in the future. Talk to a conservator if you’re not certain that you’re doing the right thing, or if you want information about training courses.

If books are damaged, be aware that some repairs can cause further damage. Sticky tapes will, in the long term, cause permanent staining. In most cases, the adhesive migrates into the paper and changes chemically, becoming insoluble and discolouring, while the tape falls off. In addition to the original damage, the paper is now badly stained as well.

Similarly, many other glues and pastes introduce acids into the paper, and many also discolour with age.

If tears are extensive and large areas of the text are missing, it is best to seek the advice or help of a conservator. But smaller repairs on bound books can be carried out in situ.

Conservators work to a code of ethics. It is important to note some of these in relation to the repair of books, so that you can think further about the choice of materials and the methods you will use. The notes which follow describe a conservator’s approach.

The treatment must be reversible, so that further treatments can be carried out in future if necessary, or so that improved techniques which may be developed can be applied.

The treatment should not disfigure or endanger the book. For example, wet treatments should not be used on material with inks that are soluble in water; and sticky tape should not be used, it stains paper badly.

The treatment and materials must match the problem. For example, heavy repair papers should not be used to repair small tears on material which is hardly used. It is better to wait till you have an appropriate repair paper.

All treatment steps should be documented with information of what was used for the repair and, if possible, with photographs of the damage before treatment.

Repairing small tears in books

Repairing torn paper or reinforcing and lining weak, degraded papers is generally a wet process— involving sticking a strong, lightweight, acid-free paper to the damaged area with starch paste.

Japanese papers are excellent for paper repair because:

- they are lightweight and strong, and their colours blend well with most papers;

- Japanese papers have long fibres—in comparison to most Western papers—this gives them their strength;

- if you decide to purchase some of these papers, ask for conservation-grade Japanese papers. Small packs of a range of papers are available from suppliers of conservation materials. You won’t need very much paper to repair small tears;

- they are usually handmade and suited for conservation. Papers such as Sekishu, Tengujo and Usumino are well-suited to book repairs because they are very fine and do not obscure the text; and

- these papers can also be water-cut, giving very soft edges to the repair patch. Knife-cut edges show as a hard ridge.

Paper can be water-cut like this:

- paper strips are water-cut using a fine brush, letter opener or bone folder, spatula and ruler;

- a stainless steel ruler is placed along the repair paper, with the required amount of paper protruding beyond the ruler;

- the wet brush is drawn along the ruler edge, wetting the paper: the paper should not become too wet;

- the letter opener, bone folder or spatula is then drawn along the ruler—to score the wet paper; and

- the strip of paper can then be pulled away from the rest of the sheet of paper.

The repair should not be much larger than the damaged area, but needs to be big enough to extend beyond the damage onto the sound paper around it. This makes a stronger repair. The feathered edges of the water-cut paper contribute to the strength of the repair, because they are all stuck down as well.

Paper strips are not always suitable for repair, and you may have to produce your own shapes. This can be done by needling out the shape using a mattress needle or the sharp end of a bone folder. Once you have made an impression in the repair paper with the needle or bone folder, apply water to the impression. Pull the shape away from the rest of the paper.

CAUTION:

Do not needle out a shape while the repair paper is resting on your book.

If you do this you will create a weak area in the book paper. You can outline the shape required on the repair paper with a soft pencil, before you commence needling.

When repairing a page of text, remember:

- wherever possible, place the repair so that it does not cover text; and place the repair on the side of the page where the repair will be least obtrusive.

The repairs are stuck in place using starch paste. It is at this stage that difficulties can arise.

Always apply the paste to the repair paper, never to the book pages. You should also allow the paste to air-dry till it is almost dry before placing it on the dry, book page. This will help to reduce the risk of cockling and tidemarks.

Once pasted, the paper can become difficult to handle, but with practice the operation becomes easier.

Once the repair is in place, it wets the book paper, which will expand where it is wet. Because only small areas are wet, you will notice that it cockles. Controlling the drying is important for these cockles to settle back down.

While drying, the repair should be sandwiched between:

- Reemay, which will prevent the blotter sticking to the repair; and

- blotters, which should be changed regularly, to ensure that the moisture absorbed by them is removed from the repair area.

This sandwich should be weighted.

It is important that the paper is fully dried. Don’t rush this, as paper can sometimes take a couple of weeks to dry fully.

CAUTION:

Repairing tears in books is not as easy as it might seem, and we strongly advise you to practise this before attempting it on a book. Wet paper will expand and distort, but with practice you can control the drying, so that the distortions flatten out without creasing.

It is also important to note that if you get the paper too wet during repair, you can produce permanent stains like ‘tidemarks’ in the paper. IF IN DOUBT DON’T DO IT!

Starch paste

Starch paste is the adhesive used most widely by paper conservators. Starch paste from various sources—for example, wheat or rice—has been used for centuries to stick paper to paper, and textiles to paper. And because it has been used for so long, we know a great deal about its behaviour. Some of its greatest advantages are that it does not discolour and it is nearly always possible to remove it without difficulty.

Starch paste is not difficult to make. You will need:

10 grams or 3.5 level teaspoons of starch, for example, Silver Star; and

100ml of water, preferably distilled or deionised.

These proportions produce a nice working consistency.

Add about 10ml of the water to the starch, and mix to a slurry.

Add more water, if required, to produce a smooth paste, and leave to soak for approximately half-an-hour.

Heat the remainder of the water in a double- boiler saucepan, or in a beaker or jar in a saucepan of boiling water. Use glass or stainless steel containers.

Add the starch slurry and cook for approximately 40 minutes, stirring constantly.

Leave to cool.

Lumpy paste is difficult to use and the lumps will be obvious, so when the paste is cool press it through a fine cloth—Terylene, for example—or push it through a fine, Nylon tea strainer or sieve a couple of times.

The paste is now ready to use. Or it can be diluted if a thinner paste is required—this is best done by mixing the paste and the required amount of water in a blender. Remember, the thinner the paste the stronger the adhesive bond.

When using an adhesive on a valued, paper-based item, it is important to know just what you’re applying to the paper and how it is likely to behave over time. Many commercially available adhesives are starch-based, but most of these adhesives also have additives such as:

- preservatives;

- plasticisers, for example, glucose, to regulate the drying speed;

- dispersing agents; and

- mineral fillers to control penetration of the adhesive into porous surfaces.

These substances, which can affect the long-term behaviour of the adhesive, are rarely listed on the label.

If you have a problem relating to the storage or display of books, contact a conservator. Conservators can offer advice and practical solutions.

For further reading

Baynes-Cope, A. D., 1989, Caring for Books and Documents, 2nd ed, British Library, London.

Bromelle, Norman S., Thomson Garry (eds.), 1982, Science and Technology in the Service of Conservation, Preprints of Contributions to the Washington Congress, 3–9 September 1982, International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, London.

Burdett, Eric, 1975, The Craft of Bookbinding—A Practical Handbook, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, UK.

Diehl, Edith, 1980, Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique, two volumes bound as one, Dover Publications Inc., New York.

Gettens, Rutherford J. & Stout, George L., 1966, Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopaedia, Dover Publications Inc., New York.

Johnson, Arthur W., 1978, The Thames and Hudson Manual of Bookbinding, Thames and Hudson Ltd, London.

Middleton, Bernard C., 1984, The Restoration of Leather Bindings, Adamantine Press Ltd, London.

National Preservation Office, 1991 Preservation Guidelines, National Preservation Office, British Library, London.

Thomson, Garry, 1994, The Museum Environment, 3rd edn, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Some of the methods described in the bookbinding manuals are not ones that would be employed by paper and book conservators. However, these books give very clear descriptions and illustrations of bookbinding styles, methods and materials. Some have excellent glossaries and notes outlining the history of different binding styles.