Objectives

At the end of this chapter you should:

be aware of how vulnerable objects are when they are being transported;

have an appreciation for providing support for objects when they are travelling;

have a basic knowledge of suitable materials to be used for packing objects for travel;

understand the need to protect objects from fluctuations in environmental conditions when moving them from one climatic zone to another; and

have some knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of different transport methods.

Introduction

The chapter on handling objects explained how objects are most vulnerable to damage when being moved—even over short distances.

The risk of damage increases when objects are moved over long distances. Objects moved interstate or overseas are susceptible to damage from:

- vibration;

- fluctuations and extremes of relative humidity and temperature;

- repeated handling;

- vibration and impact during loading and unloading from trucks and planes;

- light and UV radiation; and

- pollutants.

When moving objects over long distances, it is important to provide adequate support for them and to take steps to minimise the risk of damage.

This chapter outlines the steps that can be taken to protect objects which are being transported.

For more information

For more information about adverse environmental effects, please see Damage and Decay.

Transporting objects

If you are going to transport objects, it is important to provide:

- full support for each object;

- protection from vibration and impact;

- protection from environmental and climatic extremes; and

- protection from light and UV radiation.

There are ways of protecting objects, whichever way you’re transporting them—whether by truck and forklift, plane, or in your car.

Preparing objects for travel

Before an object travels, it is important to determine whether it is fit to withstand the rigours of the journey. Access to collections is a high priority and it is sometimes difficult to turn down requests for loans. But if an object is too fragile to travel, it should not go. Remember, if it is irreparably damaged, no-one will have access to it.

Once you have decided that the object can travel, make sure you know:

- where it is going and when;

- who will take responsibility for it while it is there;

- what the environmental conditions are like at the destination/s: if your object is fragile and likely to be damaged by adverse conditions, specify that the borrower meets your requirements;

- how it is travelling, which may affect the way you pack it and the size of the crates or packages;

- whether insurance has been arranged; and

- who is paying for packing, transport and replacement if necessary.

Loan agreements are often drawn up between lenders and borrowers, to cover these and other issues.

For more information

For an example of a loan policy, please see the chapters Purpose and Policies and Aquisitions and Significance in Managing Collections.

When you are happy with arrangements and the object is being prepared for travel, it is strongly recommended that you document its condition before it leaves your care. No-one anticipates a confrontation over responsibility for damage, but it does occur and it is important to have accurate records of the object’s existing condition, including damages and repairs, before the item leaves.

If the item is going to a number of venues, it is wise to have condition reporting documents that travel with it, and which are filled out on arrival and departure from each venue.

For more information

For more information about documenting the condition of objects, please see the chapter Collection Surveys and Condition Reporting in Managing Collections.

When objects must travel, it is important to protect them from, among other things:

- fluctuations and extremes of temperature and relative humidity;

- vibration and shock;

- impact;

- getting wet;

- theft; and

- getting lost.

For more information

For more information about adverse environmental effects, please see the chapter on Humidity and Temperature in Damage and Decay.

There are a number of ways of protecting objects for travel and they will be outlined in the following sections.

The choice between the various methods will be determined to a large degree by:

- the number of items travelling;

- their weight;

- how they are travelling;

- their uniformity of shape and size;

- your preferences for the protection of items from your collection.

Transportation methods

There are four possible options for transport—air, road, rail and sea.

Air, rail and sea will involve some road transport as well, because the crates will have to travel to and from the airport, railway station or sea port.

In Australia, sea transport is rarely a possibility and is certainly not recommended for valued works; it is very slow and it is difficult to protect works from climatic fluctuations and from salt.

Rail transport is not recommended either. It is difficult to supervise and generally involves items travelling for longer periods and over longer distances than road journeys between the same towns.

The other two options, air and road, have advantages and disadvantages that are important to assess when arranging transport for your collection.

If you are arranging to send objects overseas, it is also important to develop a good working relationship with a reputable international freighting agent, preferably one with experience in shipping museum objects and artworks.

Transporting your collection successfully requires effective communication between all parties. Always document all discussions—personal and telephone. Also make sure that you confirm with the company what was discussed, and any agreed procedures and outcomes.

Air transport

For items which have to travel interstate, air transport is a viable option. The speed of air transport makes it very convenient—a crate can be loaded on an aircraft in Perth and unloaded in Sydney on the same day. This greatly reduces many risks—including security, vibration and changes in humidity and temperature—provided safe handling can be ensured.

The speed and convenience of air transport are greatest between major cities. Air transport between regional areas is not so easy, especially if the area is serviced only by small aircraft.

If you are considering air transport, please note the following points.

It is important that valuable objects travel in pressurised compartments. This always happens on domestic passenger flights and on freight flights.

Insist that the crate travels the right way up in the aircraft. This can be difficult to ensure unless you actually supervise the loading of the aircraft. Crates for paintings should always travel in the direction of flight to minimise vibration. If crates are loaded so that the canvasses are perpendicular to the direction of flight, the canvasses are likely to flex considerably during take-off and landing.

Supervising the loading of valuable cargo is not difficult to arrange at Australian airports, especially if the cargo is to be accompanied by a courier; but it can be very time-consuming. Most cargo is loaded about 5 hours before flight departure.

Air transport involves many levels of handling. The crate has to be trucked to the air cargo depot, then loaded onto a pallet or container, then loaded into the aircraft. This is then repeated in reverse at the destination. So much handling provides many opportunities for accidents, especially if the crate is so large that it requires a forklift.

It is difficult to control where the crate is stored between connecting flights; so there is always the possibility that your valued objects will be left on the tarmac in the rain or the blazing sunshine for several hours.

Airline schedules are always changing, especially in the allocation of aircraft. You will need to keep up-to-date with the schedule changes if your crate will fit on only one type of aircraft.

International shipments

If international shipments were easy and safe, there would be no need for couriers. If you are the courier, you’re there to deal with the things that go wrong, so don’t be surprised when they do.

The one overriding thought to keep in mind if you are involved in arranging this sort of transport is that something will go wrong: so expect it and plan for it.

Good freighting agents invariably have good relationships with airport staff and may be able to achieve results that you can’t.

Make sure that the freighting agent understands your requirements and that you know the full details of how the shipment will be handled and cleared through Customs.

Make sure your freighting agent knows when there are public holidays in the countries through which your shipment is travelling.

Road transport

Road transport is the most common form of transport used in Australia.

The options available include:

packing up your objects and putting them in your car;

placing a parcel with the local express courier service; and

arranging for a dedicated air-ride truck to carry your freight door-to-door.

Remember that double-handling will occur if you use a regular transport service. The items will be collected by the freight company, then taken back to their depot and placed in a larger vehicle with other freight. This will happen even with specialised art shipment companies, unless you make special arrangements for a dedicated vehicle. Additional unsupervised handling involves additional risks.

A dedicated vehicle is the best option for large shipments, but this can be very expensive. A dedicated vehicle will carry only your freight and should travel directly from pick-up to set-down, with no depot handling.

Most interstate road transport vehicles stop during the trip for rest breaks. If your shipment is particularly valuable, make sure that there is adequate security during these breaks. Some freight companies have arrangements with country police stations for secure lock-up overnight.

There are many different types of trucks in use for freight handling. Make sure that the truck being used is covered, even for local trips. If there is a gust of wind, a sudden shower or you drive past a garden sprinkler, your objects could be badly damaged if they are on a flat-bed truck or in a ute.

If the objects or the packing are large or heavy, a truck with a platform lift—sometimes called a tail gate or tail lift—will be necessary. Alternatively, you will need to arrange for a forklift and a qualified driver to be available at both ends of the journey.

Some freight companies, especially those that handle artworks or computers regularly, have air- ride vehicles. These trucks have special suspension systems which greatly reduce vibration. Some researchers suggest that transport in a dedicated air-ride truck is safer than air transport. For large touring exhibitions this is certainly true.

Valuable objects are sometimes transported locally uncrated and unpacked or soft-packed.

This is recommended only when an experienced, reputable, art-handling company is used, and only for short journeys where there is no additional handling or changing of vehicles.

When travelling like this, the objects should be sitting on vibration-absorbing padding, and firmly tied with padded straps to one wall of the truck.

The objects should be packaged so that nothing can touch them directly. For the safety of your objects and your driver, don’t travel with unsecured items, such as trolleys, blankets or parcels, in the truck.

Sometimes it is possible to arrange last pick-up, first set-down transport with a company. Accurate crate dimensions have to be given to the freight company. They load their semi-trailer for the trip, then collect your crate last, before setting out.

This avoids the depot handling phase, but can be hard to organise and, even if agreed to, may not always happen.

Small objects travelling in your car

Even if you are transporting small items over small distances in your car, it is important to protect them. You need to provide:

adequate support;

protection against vibration and impact; and

protection against climatic extremes and fluctuations.

Pack the items well. When you place the packaged items in your car, make sure they cannot move around.

Three-dimensional objects, including framed works, should be wrapped with protective packaging material such as Cellaire foam padding.

Unmounted, small- to medium-sized paper items should be sandwiched between acid-free boards and then wrapped.

If packing more than one piece of paper, interleave each one with acid-free paper or tissue. If the items are different sizes, interleave them with acid-free board cut larger than the largest item. Large, flat items can be rolled.

Small, three-dimensional objects, once wrapped, can be placed in a box.

Packing material should be placed around the objects so they don’t move around. The packaging materials will absorb some vibration.

Small, flat items and rolls can be placed on the seat; but they should be held in place or secured in some way, so that they can’t move around or fall off the seat.

Ensure that there are no other things in the car which can move around and damage your objects.

Don’t carry valuable items on flat-bed trucks or in the back of utes.

For more information

For more information on rolling flat items, please see the notes under the heading Rollers in this chapter.

When transporting items to and from different climatic zones:

Provide them with adequate protection to buffer them against the climatic change.

It is important that they are not forced to adjust to a different climate quickly.

On arrival at their destination they should be allowed to gradually condition to their new environment. The crates should remain unopened at the destination for a full 24 hours. This allows the local climate within the crate to gradually adjust to outside conditions.

This should also be done on the return journey.

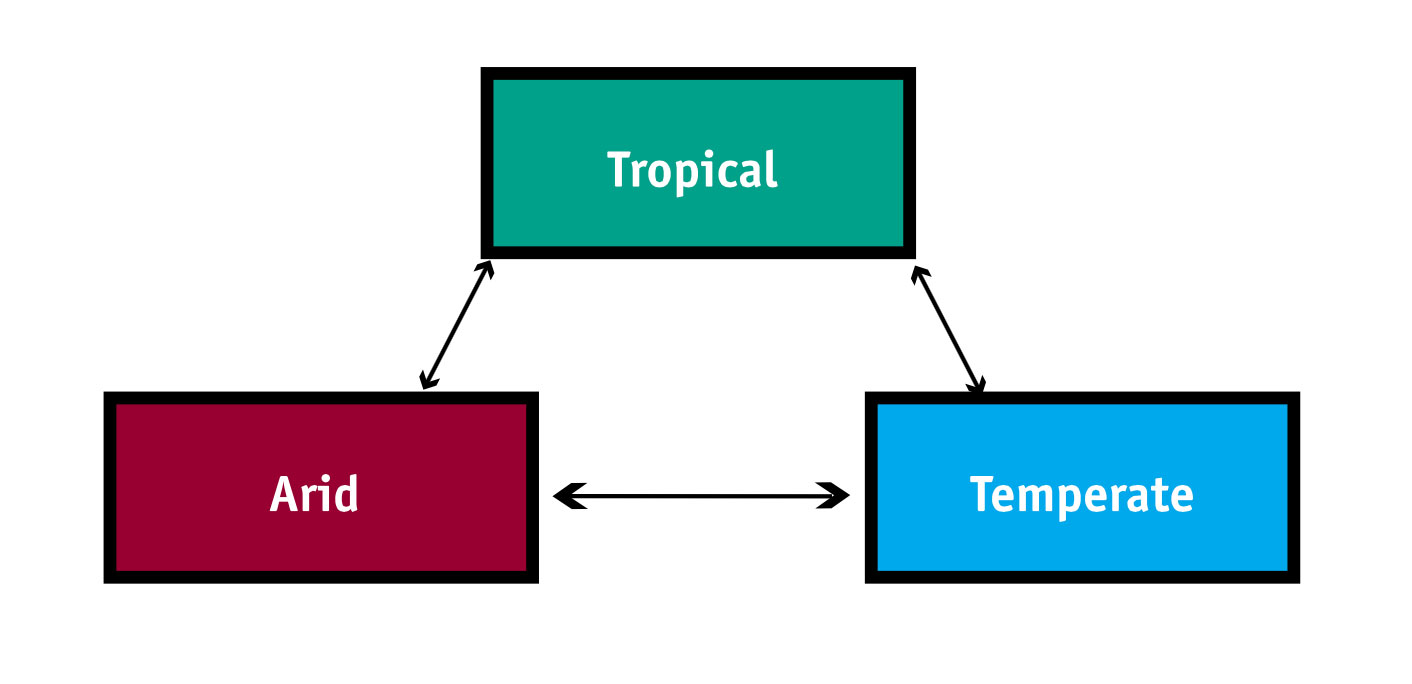

- If the objects are travelling from one extreme to the another, for example from a tropical to an arid climate, it may be advisable to allow more than 24 hours for conditioning at each end.

Crates

The safest way to transport an object is in a properly built and suitably padded crate.

There are many different crate designs and numerous competent crate builders. It is generally more cost-effective to use an established crate builder than to build your own crates.

When designing a crate, it is important to remember that it has to travel. It is very easy to get carried away designing a crate to fit, for example, all fifteen paintings in an exhibition, and finish up with a huge box which does not fit through any doors and cannot be lifted except by crane.

Remember to take into account the size of the doors at your museum, gallery or library and at the destinations: you don’t want to have your precious objects being loaded and unloaded on the footpath or in the car park because they are too large to get inside.

Do take into account the floor loading capacity of the building if you need to use a forklift or scaffold.

When calculating the capacity of the crates, remember it is always easier to find two people to lift a crate than three. Think about the final weight of the crate. Building a crate which is just a little too heavy for two people to carry safely will place the people and the objects at risk.

If you need to air-freight the crate, there will be additional limitations on the crate’s size— sometimes these are surprisingly restrictive.

What makes a crate?

Most crates consist of:

an outside shell of timber forming a box;

a waterproof lining, which can be plastic sheeting, tar-paper or a waterproof insulation layer such as sisalation: the better the insulating properties of the crate, the better it is for the objects being transported; and

a lid which is well sealed—this seal is usually a foam or rubber gasket;

Painting the exterior of a crate is important because it provides an additional waterproofing layer. Also, if you paint it white, it will reflect light and keep the interior cooler. White has a curious psychological effect—people handling a white-painted crate consider it to be more fragile and so handle it more carefully than other crates.

Crates usually open at the top if they are small, or at one side or end if they are large. The lid can be fixed with either screws or bolts set in threads.

Threaded bolts are better than screws, because they can be opened and closed many times without compromising the security of the fixing. Once screws have been removed and replaced several times, they become loose and can work free during transport.

Don’t use nails to fix the lid—the objects in the crate will suffer the vibration of hammering when the lid is being fitted.

The interior of the crate will vary depending on the nature of the items to be transported, but must always contain foam padding to absorb vibration. The padding is put in strategic positions to ensure that maximum vibration absorption is achieved. The best padding consists of foam blocks made of layers of foam with different densities, so that different levels of vibration are absorbed.

Good-quality, dense foam forms the base of the block, with softer, more compressible foams on top. Using only low-density, soft foam will result in small vibrations being absorbed, but not sudden shocks such as when a crate is dropped.

Foams such as Plastazote and Evazote polyethylene foams are good foams to use; they have good densities and are relatively inert materials which won’t deteriorate or give off harmful gases. They are relatively expensive to buy by the sheet; but remember that you don’t need to pad the whole surface of your crate, only the strategic points.

It is important that paintings and framed works on paper travel vertically. Crates for these types of objects are generally designed to take several works in slots made to fit the individual works. The slots keep the works separate and minimise movement.

Packing three-dimensional objects is a much more complex procedure. Each object must be assessed carefully to determine the appropriate crating system and the type and amount of padding and support that will be required.

When you are ready to pack

It is critical that crates are packed indoors if at all possible, so that the objects are exposed to minimal changes in temperature and humidity.

Crates must be labelled, either with stickers or painted symbols on the crate, to indicate which way up they are to travel. ‘Rain’ and ‘sun’ protection symbols and ‘fragile’ signs should also be applied. There are standard international symbols for these things: arrows, umbrella, broken glass.

Sophisticated monitoring of artworks in transit is possible. There are numerous digital recording devices available which can be placed in the crate to record temperature and humidity changes or vibration extremes.

Simple stick-on devices called ‘Shockwatch’ can also be used to record whether a shock above a certain level has been sustained by the crate. Sometimes simply labelling a crate stating that a Shockwatch indicator is enclosed is enough to encourage more careful handling.

Travel frames

Paintings which are unframed or have frames with delicate gilded surfaces or ornate mouldings should always travel in travel frames. This may seem like an unnecessary expense, but in the long run it provides many savings.

It is much easier to crate several works in the same crate if they are in travel frames of similar size. The travel frame can be much larger than the painting, or you can put several small paintings on one large travel frame.

Travel frames make it much easier to pad the crate, and greatly reduce the risk of damage to fragile or gilded surfaces.

An unframed painting can also be stored in its travel frame until it actually goes on the wall, preventing damage from handling fragile edges.

Basically, the rule for travel frames is that you use them whenever you don’t want any part of the painting or frame to touch the crate.

When paintings are fitted in travel frames, special fittings are used. These are either Ozclips or ‘doovers’, both Australian inventions. Ozclips can also be used to hang the painting on the wall in the exhibition.

Paintings fitted in travel frames should rest on layered foam blocks, so that additional vibration absorption is provided. When the painting is fitted into the crate, the blocks of foam should be slightly compressed.

Rollers

Very large, unstretched paintings, textiles and large maps or works of art on paper should be transported rolled. Some unmounted works on paper are also transported rolled.

It is very important that paintings are rolled the right way, painted side out, and that they are properly interleaved and the roller properly padded. If the paint layer is rolled inside, the paint compresses and develops creases which remain in the painting after it is unrolled.

The roller should be as large in diameter as possible, because you want the item to uncurl easily when it arrives at its destination. A very large Aboriginal acrylic painting which travelled to the USA in the South Australian Museum’s Dreamings exhibition was rolled on a roller more than one metre in diameter. This size roller is not always possible or practical; but a good rule is to make the roller as large as will fit in a crate of reasonable size.

Rollers can be specially made of light-weight materials, such as Ribloc, or you can buy PVC pipe. A 300mm diameter pipe is a good size for most works.

If you are using a cardboard tube as the roller, pad it out to as large a diameter as possible.

Rollers should be covered with a layer of padding, either polyethylene foam such as Plastazote or Cellair, or Dacron wadding covered with clean, white, cotton fabric, to compensate for any irregularities in the painting’s thickness.

It is best to roll the object with an interleaving layer of Tyvek for added protection, especially if there is more than one item on the roller.

To transport works on paper using a cardboard tube, roll the paper around the outside of the tube. DO NOT roll the paper and place it inside the tube. It is extremely difficult to remove from the tube and the edges of the paper often get damaged in the attempt.

Before rolling the paper around the tube, cover the cardboard tube with acid-free paper. Another layer of acid-free paper should be rolled onto the tube with the work. Several protective layers of paper, padding and Tyvek should be added to the outside of the roll.

When rolled, the object should be tied firmly, but not tightly, with cotton tape in several places along the roll.

Packing instructions

It is always important to include unpacking and repacking instructions and an inventory in each crate. If possible, these documents should also be posted or faxed to the receiver before the crate leaves your museum, gallery or library.

Even if the packing and unpacking seems obvious to you, it is still worth spending the time writing instructions and a contents list. The person opening the crate at the other end may never have seen a crate like yours.

Labelling

Labelling is critical whichever transport system is selected. No matter how many forms have been filled out, make sure that there are labels firmly fixed to at least two sides of each crate, stating the originating and destination addresses, as well as contact names and telephone numbers.

Appropriate labels should be attached to indicate, for example, that items are fragile and that they need to be kept upright. If you don’t provide these labels, the people handling the objects and crates will not know that they have to be careful.

It is important to label individual parcels and packages within crates as well. If many items are arriving at the destination at the same time, proper labelling makes it much easier to keep track of individual objects.

Use strong, sturdy labels that are securely fixed. Post-It notes are not good enough—they will fall off.

Soft-packing framed items

Framed items can be shipped with a reasonable degree of safety if they are packed well.

It is important to include a solid barrier on each side of the work, to provide some protection against impact. Various materials can be used, including cardboard, Foam-cor, Gator Foam, Masonite, Artcor and Perspex, depending on the level of protection desired. These materials should not be in direct contact with the work, because some of them are acidic and/or could stain the work. They have been selected for their resistance to impact, not for their archival qualities.

Before shipping a framed work, exchange the glass for Perspex or Plexiglas—except for chalks and pastels because the static electricity generated by plastics such as Perspex and Plexiglas attracts the loosely bound pigment. Glass can break and damage the item in the frame. If this is not possible, tape the glass with masking tape, so that if it breaks it does not fall into the work and cause damage.

The tape should be on the glass only. For small frames, one strip of tape vertically in the centre of the glass, one horizontal strip and one strip on each diagonal will be sufficient. Larger frames will need more.

Remove the screw-eyes and hanging wire from the back of the frame, because they can damage other items and prevent the packing materials from being in contact with the frame.

Cut two panels of solid, barrier material equal to the outside dimensions of the frame. Using a soft- packing material such as Cellair, pad the area above the glass or Perspex until it is flush with the top of the frame.

Wrap the frame in brown paper to protect it from abrasion. Place the frame between the two solid panels.

Wrap Cellair around the frame and panels, and seal the ends with masking tape. Cellair is a suitable packing material—it absorbs shock and provides a waterproof barrier. It should not be used for long- term storage as it can seal in moisture.

Wrap the whole package in brown paper and tape the ends. Finally, seal the package securely with masking tape and apply labels.

To protect ornate, fancy-cornered or fragile frames, place sponges or other soft packing materials on solid areas of the frame. The top solid panel will rest on the sponges, rather than on the fragile or ornate part of the frame.

CAUTION:

If you are using bubble wrap to pack your items, put the bubbles on the outside. Bubble wrap can transfer a pattern to paint layers and gilding.

If you have questions about transporting objects, contact a conservator. They can offer advice and practical solutions.

For further reading

Kelly, Sara, 1994, Travelling Exhibitions—

A Practical Handbook for Non-State Metropolitan and Regional Galleries and Museums, National Exhibitions Touring Support for Victoria, Melbourne.

Rennie, Sarah, 1997, ‘Concerning Works of Art’ in Australian Registrars Committee Newsletter, Sept 1997, Australian Registrars Committee, Canberra.

Richard, Mervin, Mecklenburg, Marion F., Merrill, Ross M. (eds.), 1991, Art in Transit—Handbook for Packing and Transporting Paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

Stolow, Nathan, 1987, Conservation and Exhibitions: Packing, transport, storage and environmental considerations, Butterworths, London.

Self-evaluation quiz

Question 1.

Which of the following statements are true?

a) Sea transport is not a favoured option because it is slow and exposes objects to climatic fluctuations and salts.

b) Air transport is quick and convenient for everyone in Australia.

c) It is wise to check to see if aircraft schedules or the allocation of aircraft have changed if your crate of objects will only fit one type of aircraft.

d) Valuable objects should travel in a pressurised compartment.

Question 2.

When transporting objects by road:

a) put them in the back of the ute;

b) provide them with support and protection from vibration;

c) you must have a dedicated air-ride truck;

d) make sure there is enough security during the driver’s work breaks.

Question 3.

When transporting objects from one climatic extreme to another:

a) it is important to buffer them against rapid climate changes;

b) you should get them out into the new conditions as soon as possible so they are ready to display sooner;

c) they should be left in their crate for at least 24 hours to gradually adjust to the new conditions;

d) check the condition of your object before departure and on arrival.

Question 4.

Which of the following statements are false?

a) Crates should be well sealed.

b) Crates should be waterproofed

c) There is no need for a contents list or packing instructions for crates because its usually obvious what goes where.

d) Crates should be padded well to protect objects from vibration and impact.

e) All of the above.

Answers to self-evaluation quiz

Question 1.

Answer: a), c) and d) are true. b) is false. Air transport is quick and convenient if you are situated in a major city or regional centre. It is not convenient for everyone.

Question 2.

Answer: b) and d). Putting items in the back of the ute is not a good idea because they will not be protected from sudden showers, garden sprinklers and wind gusts. It is not absolutely necessary to have a dedicated air-ride truck, especially if you are transporting only a few items.

Question 3.

Answer: a), c) and d). If you follow b), you will almost certainly cause damage.

Question 4.

Answer: c). A contents list and packing instructions should be included in the crate. The method of repacking the crate is not always obvious.