Objectives

At the end of this chapter you should:

be familiar with the structure and components of various types of paintings;

understand possible sources of damage for paintings; and

know how to frame and hang a painting to ensure proper protection from damage.

Introduction

Early frames were simple affairs. They were usually made from single pieces of wood which were generally either gilded or left plain. They were originally used to protect the fragile edges of panel altarpieces. Then, as paintings became more secular, frames became more decorative and were designed to complement the architecture surrounding them.

So we can see that the frame on a painting serves two purposes:

it has an aesthetic function—it enhances elements of the painting and unifies the painting with its environment; and

it also serves as a protective device, providing a physical barrier between the environment and the artwork.

Additional protective components can be added to the frame to:

- protect the back and front of the artwork from knocks and abrasions;

- minimise the effects of vibration and movement;

- enable the work to be hung securely;

- facilitate handling; and

- protect the work from dust and pollution.

Many paintings, however, do not have frames, or they have flimsy and inadequate original frames. Such works are more difficult to protect; but if you keep the basic principles in mind, you can provide protection for all paintings.

It is important to note that not all frames are protective. While a good-quality, well-constructed frame will provide protection for a painting, a poorly made frame, or one which is not properly fitted to the work, can cause damage.

This section discusses good protective framing practice; it looks at the types of framing systems which are relevant for each type of painting structure and gives general information to help you prolong the lives of the paintings in your care.

Structure of paintings

In order to discuss the possible damage to paintings and to take steps to reduce that damage, it is important to know something of the structure of paintings and the range of materials which can be used to produce them.

Paintings consist at the very least of two layers:

the support layer on which the image layer rests—this can be canvas, wooden panelling, or Masonite; and

the image layer—oil paint, acrylic paint or paint in combination with other materials.

If the support and the image layer are not securely bonded, then any movement in the support will damage the paint layer.

Most paintings are more complex than this and have many more parts in their structure. A traditional painting on canvas will usually have:

a sized support—in many cases canvas sized with skin glue;

a priming or ground layer;

the paint or image layer;

a varnish layer; and

an auxiliary support which provides physical support for the support layer.

Supports

The term ‘support’ refers to the layer which carries or supports the paint or image layer.

Paintings can be produced on any type of support.

Traditionally, most supports have been made from linen canvas or wooden panels.

In the 20th century, linen canvas has often been replaced by cotton duck, and wooden panels with compressed particle board such as Masonite.

Artists are creative beings and there are a wide range of materials which have been used in the name of art! They include:

rigid wooden supports such as particle board products like chipboard or Masonite or the traditional wooden panels;

rigid supports made from a range of other materials such as glass or metal;

lightweight cottons or Nylon loosely stretched, which some artists use to give a feeling of fluidity;

paper glued onto canvas;

canvas.

The priming and ground layers

Priming and ground layers are used to:

- provide a good physical support for the paint layer; and

- provide a surface to mask the texture of the support. If there are no priming and ground layers, it may be possible to see the texture of the support through the paint.

A good ground layer physically keys in the paint layer as it is slightly porous.

The ground layer, however, should not be very absorbent. It must be slightly resistant to the paint, otherwise brushstrokes will not be clear and will sink into the ground.

The support is sized, usually with rabbit-skin glue; and then the ground layers are applied.

Works on canvas usually have two ground layers, although having one or three is not uncommon.

If the ground layers are not well bonded to the support, then movement of the support may lead to a delamination or cracking of the ground.

In addition, if the ground layers are not properly prepared or do not provide a secure base for the paint layer—they may not be porous enough to hold the paint for example—then problems with the paint layer will occur.

A traditional ground was usually made from lead white or a chalk gesso. Acrylic grounds are now common. While grounds are generally white, some artists, John Constable for instance, favoured coloured grounds.

The layers of size and ground can be very reactive; and if they are wet they will cause severe damage to the paint layers.

The paint layer

The paint layer or image layer can be made up of paint and a number of other materials, including paper or found objects in collage.

Oil paint is the traditional paint medium, however, in more recent times synthetic materials such as acrylics and alkaloid resins are common.

Oil paint dries by evaporation, and then by a chemical crosslinking process. This means that it becomes less flexible as it ages.

The varnish layer

Varnishes are applied on top of the paint layer. They are applied as liquids and dried to produce clear, tough films.

They protect the paint layer—to a degree depending on their composition—from physical damage and chemical attack.

Varnishes also have an aesthetic function: they smooth out the unevenness of the paint surface so preventing light being scattered when it is reflected. This gives the colours in the work a more saturated appearance—the colours appear darker and have greater depth.

It is important to note that further paint layers and transparent coloured layers known as glazes may be applied over the varnish layer. This technique produces an illusion of depth.

A range of materials have been used as varnishes. Among the most stable are:

Dammar dissolved in turpentine—this is an example of a traditional varnish made from natural resins dissolved in solvents; and

acrylic resins dissolved in petroleum spirit.

Auxiliary supports

Traditionally, paintings on canvas have been attached to auxiliary supports—usually a stretcher or a strainer—using staples or tacks.

The purpose of the auxiliary support is to secure the canvas and keep it taut. It is important to keep the support as taut as possible—loose supports will undergo far greater dimensional change in response to fluctuations and so are much more vulnerable to damage.

A stretcher differs from a strainer in that the corners of a stretcher can be keyed out, thereby tightening the canvas.

The corners of the stretcher are adjustable, enabling the dimensions of the stretcher to be enlarged to tighten the canvas. This is done by pushing the keys further into the keyholes, and expanding the corners.

CAUTION:

Because inappropriate tightening of the canvas can cause damage, you need to know what you are doing, or be shown by a conservator, before you commence keying out a work.

A strainer is a wooden frame which does not have adjustable corners. Therefore if the canvas becomes loose over time, it cannot be made taut again without being re-stretched—this is a job for a conservator.

Examples of other auxiliary supports include:

cradles placed on the backs of panel paintings; and

wooden frames used to secure Masonite supports.

What are the most common types and causes of damage?

As with most cultural material, the deterioration of paintings is caused by physical damage and chemical activity—usually in combination.

Physical damage is very obvious and includes:

Tears and breaks. For example, many canvas paintings are damaged when people are working near the paintings and accidentally put the handle of a broom, a ladder etc. through the canvas. This is not uncommon.

Cracking of varnish and paint layers because of movement of the support, due to:

vibration during handling and travel;

impact when a painting is dropped, knocked or falls off a wall; and

fluctuations in relative humidity. Both canvas and wood take up and release moisture as the relative humidity fluctuates. This produces dimensional changes which can lead to cracking of the paint and varnish.

Separation of the different layers of the painting structure. This can because by fluctuations in relative humidity and/or to impact.

Softening of the varnish layer in high temperatures. The varnish can become sticky and any dust or dirt on the surface may become permanently attached to the painting.

Warping of the stretcher due to extremes and fluctuations in relative humidity, and lack of proper support in storage or display.

Insect attack, for example, wooden stretchers can be attacked by borers and canvas and cardboard supports can be attacked by silverfish.

Dust and dirt can distort paintings if allowed to collect between the lower stretcher bar and the canvas. This can lead to distortion of the paint layer. Dust will also take up and hold moisture, thus creating a localised area of high humidity— this can lead to localised dimensional change and overall distortion.

Chemical deterioration can be very damaging and will often mar the appearance of paintings. Chemical damage to paintings includes:

Colour change and fading of pigments when exposed to light and UV radiation. Oil paintings are often considered to be quite stable in light, but some pigments and glazes are particularly susceptible to light damage.

Discolouration of the varnish. This may be due to exposure to light and UV radiation and/or because of the natural ageing of the particular varnish.

Deterioration of some components of the painting where poor-quality materials have been used or where the painting has not been properly structured.

Reactions between incompatible components of the painting. This is more likely to occur when the painting is a complex collage made up of a combination of paint and a number of other materials.

Cracking or movement of paint layers due to the unstable nature of one or more of the components of the painting. Bituminous additives in paint are an example of one of these unstable materials.

Mould attack. All components of paintings are susceptible to mould in high-humidity conditions.

Changes due to the action of atmospheric pollutants, for example:

colour change in pigments;

breaking down of structural components leading to loss of strength; and

alterations in solubility characteristics of paint films and varnishes.

The do\'s and don\'ts of handling paintings

Because paintings are such complex structures, it is important to understand correct handling procedures. Remember, a paint surface may receive a knock and appear to be unharmed. But over time movement in the canvas will cause this weakened area to crack. It can take a decade or longer for a crack to appear after a knock.

Handling stretched paintings and framed works

It is very difficult to properly support and protect paintings if you carry more than one at a time. It is important that you always carry only one painting at a time.

Before moving any painting:

Check that there is no flaking paint and that the work is secure in its frame.

Check that there are no loose pieces on the frame. If there are, consult a conservator.

Make sure you know where you are going with the work, and you have checked your path to make sure it is clear and all doors are open, or that there are people available to assist.

If there is flaking paint on the painting, leave it face-up and consult a conservator. If you have to move it, carry it flat and face-up, so that you don’t lose any paint while you are moving.

Do not touch the canvas or the paint surface directly.

Wearing white, cotton gloves while handling paintings and frames is advisable, particularly when handling gilded frames. Gilt surfaces can be permanently marked by perspiration and oils from your skin.

If your canvas painting does not have a backboard, check that the stretcher wedges are secured. They can do a lot of damage if they fall between the canvas and the stretcher.

Always hold paintings at points where the frame is strong. Ornate frames are especially vulnerable to damage. Never grip them by any of the ornate areas of the frame, because they may not be very strong and could break.

Never carry a painting by the top of its frame or stretcher. Carry it with one hand beneath and one hand at the side; or if it is small, one hand on each side. Carrying frames from the top member is dangerous and can cause the mitres to become loose and decorative elements to dislodge.

If the work is unframed, it is better to move it using handling straps or a travelling frame. Both of these allow you to carry paintings without the need for you to touch the paint surface. If neither of these are available, then carry unframed, stretched paintings on the outer edges without touching either the front or back of the canvas. Don’t allow your fingers to touch the paint surface.

Don’t put your fingers around the stretcher bars, or between the stretcher and the canvas, because you could cause the canvas to bulge and the paint to crack and flake in that area.

Remember to carry wrapped paintings with extra care, because you cannot see what you are touching.

Before putting a painting down on the floor, ensure that there are padded, wooden blocks or foam blocks in place where you wish to place it. These blocks provide a softer surface than the floor and keep paintings up off ground-level.

When you put the painting down, do not set it down on one corner: always set it down along one complete edge.

A large painting must be moved by two people regardless of the weight involved. Never attempt to move a large painting alone. When two people are working together, make sure you both agree on the way the painting is to be moved.

If you are moving paintings on a trolley, it is wise to have two people to accompany the loaded trolley. With two people, you have one to hold the paintings in place while the other can open doors, etc. If one person tries to do everything at once, accidents are likely to happen.

Trolleys should be padded to prevent damage to frames.

If any damage should occur during the move, carefully collect and save any pieces, no matter how small—even tiny paint flakes—and document the damage.

If you are hanging a painting, check that the hanging devices and the wall on which the painting is to be hung are secure. Paintings can be very badly damaged if they fall off the wall.

When you are framing or deframing a painting, make sure that you have a clean, padded surface on which to place both the frame and the painting.

Moving framed paintings with glazing

‘Glazing’ usually refers to the glass or Perspex sometimes used in framing systems for paintings.

Glazed artworks should be carried with care:

acrylic glazing such as Perspex is easily scratched; and

glass can break if dropped or knocked.

If you are transporting paintings glazed with glass, tape the front of the glass with masking tape. This will hold the pieces of the glass together, should it break, and lessen the risk of damage to the work.

The tape should be on the glass only, and should not extend onto the frame because it can remove paint or other finishes when it is removed.

For small frames, one strip of tape vertically in the centre of the glass, one horizontally and one strip of tape on each diagonal will be sufficient. Larger frames will need more.

Fold the tape back on itself at one end of each strip, to provide yourself with a grip for easier removal of the tape.

Remove the tape as soon as possible after the move. Pull the tape off at a very low angle, so that you don’t make the glass flex too much. This could cause it to break. Remember, pull gently.

It is better not to tape Perspex or Plexiglas as:

the tape can be very difficult to remove;

it can leave adhesive residues which cannot be cleaned away; and

there is, after all, really no need to tape Perspex or Plexiglas because they won’t break and shatter like glass.

Handling unstretched paintings

Not all paintings are stretched and framed. Many paintings are now sold and kept, unstretched. Because the canvas is not kept taut, these paintings are particularly vulnerable to damage caused by movement of the support.

Unstretched paintings can be quite difficult to handle. If they are allowed to flop or move too much, the paint can begin to come away from the surface of the canvas; so it is very important that unstretched paintings are well supported.

If the paintings are small enough to be moved flat, put a rigid support under them so that they can be handled easily without flopping and distorting. A sheet of Foam Cor or a strong mount board is suitable.

Larger unstretched paintings may need to be rolled to be carried, and transported.

If you are going to roll a painting it is very important that paintings are rolled the right way—painted side out—and that they are properly interleaved and the roller properly padded. If the paint layer is on the inside when the painting is rolled, the paint will become compressed and will develop creases, which will remain in the painting after it has been unrolled.

The roller should be as large as possible in diameter—at least 200mm. For example, a very large acrylic painting which travelled to the USA in the South Australian Museum’s Dreamings exhibition was rolled on a roller more than one metre in diameter. The larger the painting, the larger the diameter of the roller should be.

Rollers should be covered with a layer of padding—either a polyethylene foam such as Plastazote, or Dacron wadding covered with clean white cotton fabric—to compensate for any irregularities in the painting’s thickness.

It is best to roll the painting with an interleaving layer of Tyvek to prevent any transfer of pigment. The Tyvek should be larger in length and width than the painting.

The rolled and wrapped painting should be tied firmly, but not tightly, with cotton tape in several places along the roll.

Rollers can be specially made of lightweight materials, such as:

Ribloc. Ask the manufacturer to make the roller with the ribs on the inside, if possible; and

PVC pipe. A 300mm diameter pipe is a good size for most works.

If you have to roll more than one painting on a roller, the paintings should be laid out flat and interleaved with Protecta Foam. Once this is done, the paintings should be rolled onto the roller all at the same time. Remember, all the paintings should be paint-side out.

Framing paintings

As already noted, frames are important protective devices. Good framing is as much common sense as anything else but certain principles should be kept in mind.

The painting needs to be protected at the front and back if possible, from damage caused by:

knocks and abrasions;

dust and pollution;

environmental fluctuations; and

biological pests.

For this reason you should provide a backing board for your paintings, and consider glazing works.

The painting needs to be protected from vibration as much as possible. For this reason the frame needs to hold the work firmly but allow some cushioning, so that if the painting is knocked the frame will take the force of the impact. The painting will need to be keyed out if the canvas becomes loose. Make sure that the painting does not fit too tightly in the frame.

Other considerations—aesthetics and history

When making any decisions about whether to retain, replace or repair an original frame, it is important to understand the history of the painting and its frame.

Many artists consider the frame to be an important part of the presentation of their work. For some it is even an intrinsic element. Keep in mind that frame styles reflect the period of the artwork and/or the design of the individual artist.

It is important to note that in some instances the frame will have been conceived as part of the original aesthetic of the work. For example:

- the 1889 9’ x 5’ exhibition is perhaps the most well known Australian example of artists making very specific decisions about their frames;

many contemporary artists have very definite ideas on the framing of their work; and

Fiona MacDonald is an example of a contemporary Australian artist who uses the frame as part of the aesthetic of her work. To replace the frame would be akin to replacing part of the work.

Many frames are important aesthetic statements in their own right and may be valuable historic items. For example, framemakers Robin Hood and Isaac Whitehead were important Australian framemakers. An original frame by these framemakers is likely to be worth a substantial amount of money, certainly in the tens of thousands for a large, ornate frame in good original condition.

In other instances the artist may have no interest in the frame at all. Works may be sold unframed or the artist may simply have a trade order with a framer.

Decisions about framing and reframing, therefore, need to be made carefully and with a proper understanding of all the issues.

Backing boards

Backing boards protect the painting by providing a physical barrier between the back of the painting and the external environment.

It is obvious that one of the most important things you can do to protect a painting is to provide it with a snugly fitting backing board. A backing board will help to protect against:

- knocks;

- changes in temperature and humidity;

- the effects of atmospheric pollution;

- lodgement and build-up of dust;

- insect and mould attack.

Various types of material can be used for backing boards. It is important to choose a material which is lightweight, but still strong enough to take knocks and to provide a physical barrier. Two materials which have been used widely in recent times are:

Foam Cor—a composite consisting of outer layers of paper and an inner layer of polystyrene; and

Corflute—a synthetic corrugate.

pH-buffered, corrugated archival cardboard and other stable materials can also be used. The abovementioned materials are considered to be more chemically stable than timber or Masonite.

If you retain a timber or Masonite backing, introduce a barrier between it and the painting. The barrier could be acid-free paper or board.

Sometimes a work will have an original backing board with inscriptions and labels. If this is the case you will probably want to retain this information. If the labels are in poor condition, you should consult a conservator regarding their preservation. All labels and inscriptions provide potentially valuable information about the work. It is important to transcribe this information into any records you keep about the painting, including condition reports.

Sometimes a backing board may hide information on the canvas.

In some instances a conservator will transcribe this information onto the backing board, noting that the original exists on the canvas.

If the back of the work has a large amount of information or you want the information to be visible, a sheet of Perspex can be used as the backing board. In this way, the work is protected while still allowing the back of the work to be viewed.

Backing boards are screwed into the back of the frame and should fit well enough to make a dust seal. They provide more protection from impact if they are attached to the frame—because the frame, rather than the painting, will absorb most of the shock.

It is important to note that backing boards should not be attached to the stretcher or strainer, because this weakens the structure and may necessitate putting holes in the canvas, which could lead to tearing.

Glazing

Glazing is a generic term and usually refers to glass or Perspex.

When glazing, you should be ensure that:

there is sufficient space between the glass or Perspex and the surface of the work, so that the paint surface will not touch the glazing. Slips and spacers should be used to provide this space. Slips are visible and can be a decorative element in the frame. Spacers are not seen;

Perspex is not used where there is any danger of the paint or image layers being affected by static electricity, for example, where there is flaking paint or where there is mixed medium such as in collage; and

you do not use glazing when framing works which have been recently varnished, because the varnish will not be able to dry properly and may develop a white bloom.

There are a number of different types of glass on the market, including very expensive, water-clear bullet-proof glass. If you want to use this glass, you should check with your State art gallery to see if they have a local supplier, as this glass is not readily available.

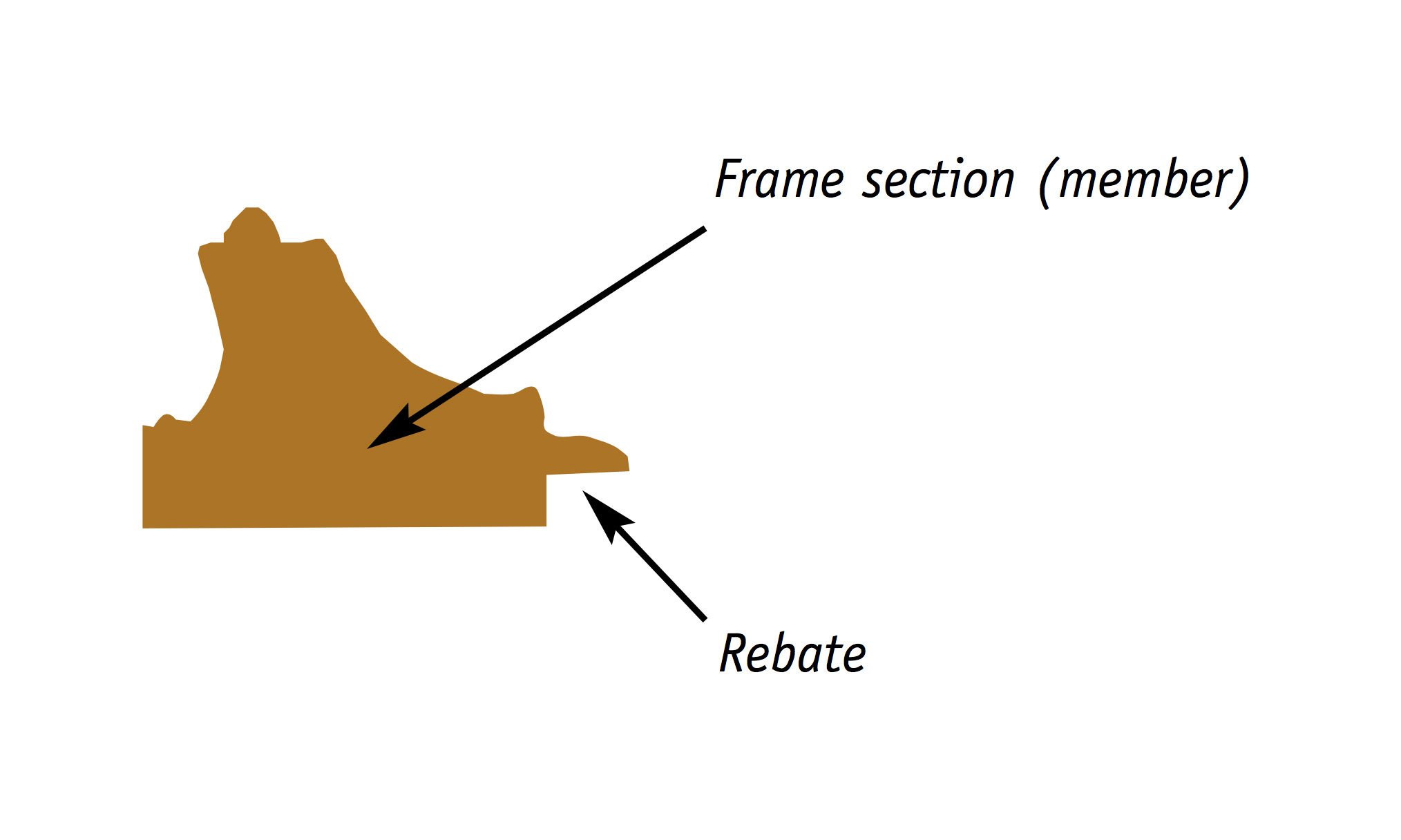

Putting the painting in the frame

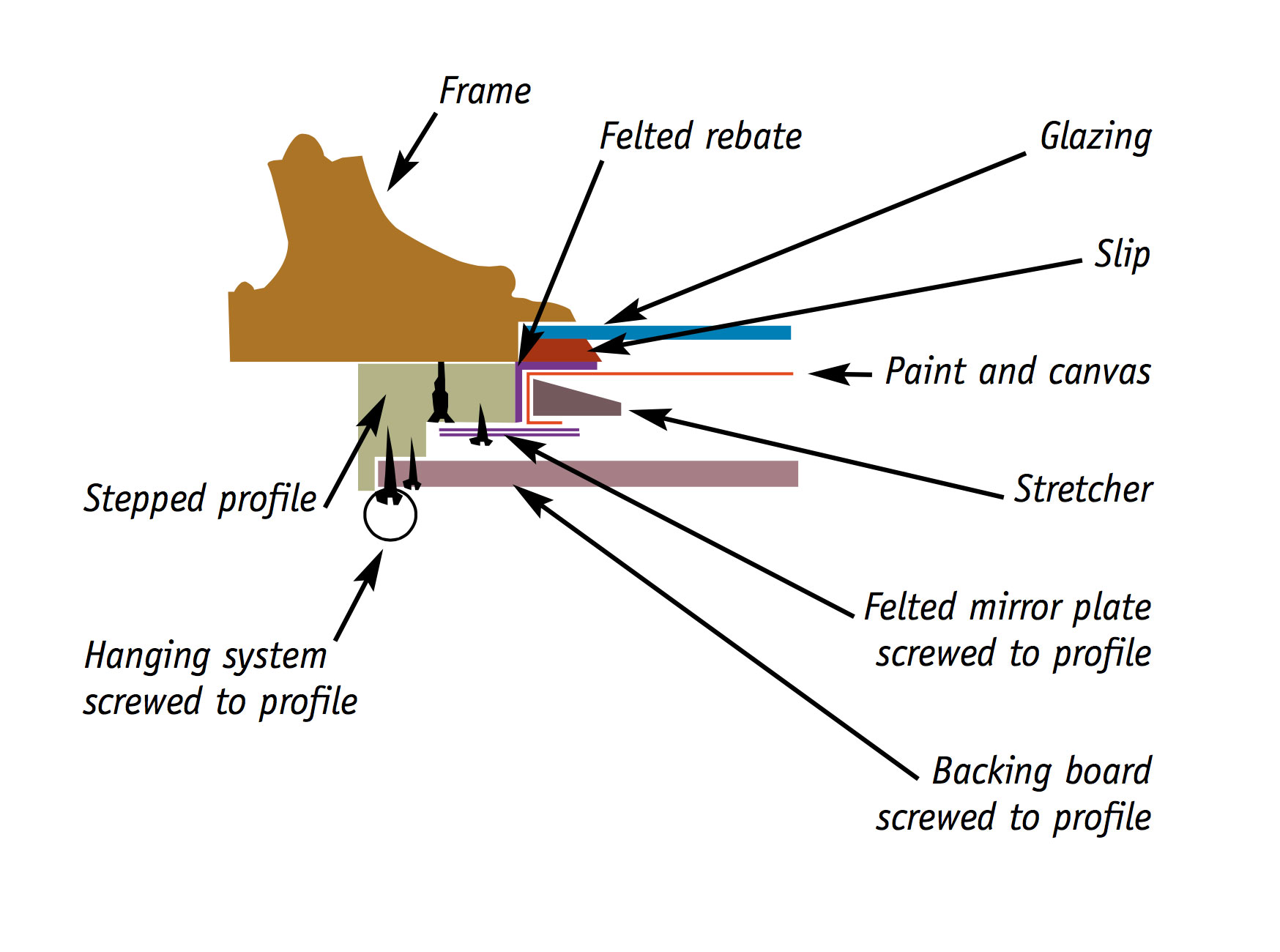

The following diagram shows how a stretched canvas painting should be fitted in a frame to provide a protected environment for the painting.

The back of the frame is built up with a profile section screwed to the frame. This increases the depth of the rebate, and provides the recessed space for the mirror clips and backing board.

The slip is necessary to ensure that the paint surface does not contact the glass.

The slip, rebate and mirror plates—that is all surfaces contacting the painting—need to be felted with either a polyester felt or an inert cushioning material such as Cellair.

If the painting fits loosely in the frame, spacers should be used to bulk out the rebate. Rag board, pH-buffered cardboard, balsa wood, cork and Foam Cor are suitable materials. These spacers should be glued to the rebate to prevent them slipping out of place and so to reduce the risk of damage to the painting.

Felted mirror plates are used to hold the painting in the frame. These can be bent slightly to hold the painting and are screwed into the profile.

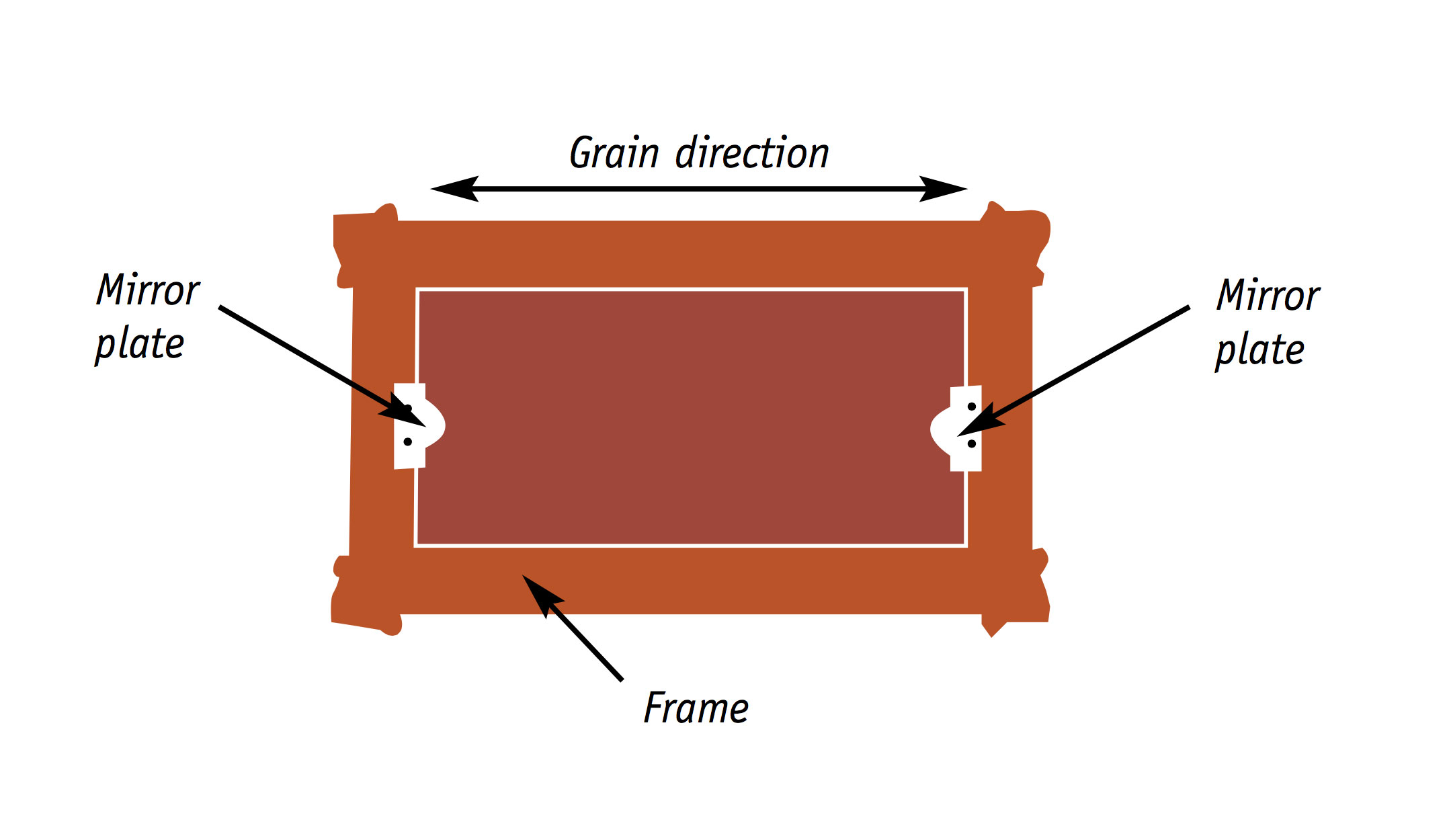

Panel paintings should be held in place by two mirror plates placed at either side of the painting in line with the grain of the wood. This means that, if necessary, there is some freedom of movement of the wood. Remember that if a panel is unable to move it will crack.

CAUTION:

You will find that many works are held in the frame with nails. Hammering nails into place causes severe vibration which can lead to damage.

Nails can also be difficult to remove without damaging the tacking edge and the stretcher. If the nails pass through the stretcher, then the painting cannot be keyed out. When reframing these paintings, remove the nails and do not replace them. Instead, use metal plates or mirror plates which can be screwed into place.

Hanging paintings securely

For safe hanging, paintings need to be secure in their frames and each frame needs to be securely hung from two points in the wall, with a hanging device attached to two points on the frame.

Paintings of different size and weight may require different hanging systems, but if you think sensibly about the problems that may arise when you are hanging a particular work, most problems can be averted.

There are two main principles to keep in mind when hanging a painting:

the work should be properly supported for its weight; and

there should be no stresses on any part of the hanging system or the painting.

Some basic principles to keep in mind are:

Use materials which will not rust. For example, you should use nickel-plated screws, brass or nickel-plated screw eyes or D-rings, and non-rusting multi-strand wire if you are using wire. If you use materials which rust, they will lose strength when they rust and your paintings will be at risk.

Ensure that the wall into which the hanging system is secured is stable and structurally sound. If possible hang works from a well secured picture rail. If this is not available, make sure that you attach the plugs or secure hooks with toggle bolts into the studs in the wall structure.

Ensure that stresses are evenly distributed across the work. If the work is large, use a shelf to take the weight.

Do not hang the painting from one point, because this will create stress across the back of the frame, weakening corners and opening mitres. On an ornate frame this may result in loss of decoration.

For a light- to medium-sized framed painting:

the work should be hung from two separate points on the wall, with the hanging device attached to two points on the back of the frame;

the hanging devices should be strong enough to take the weight of the work without becoming stressed or warped; and

if you are using hanging wire, ensure that it is not crimped as this will be a weak point.

For hanging a heavy work:

use a shelf to evenly distribute the weight along the bottom of the work, and use the hanging devices to secure the work against the wall; and

if necessary provide four or more hanging devices, such as mirror plates screwed to the frame and then into secure sections of the wall.

Hanging devices

Hanging devices need to be strong and rust-proof. D-rings are preferable to screw eyes because they are less likely to snap and are not weakened by the screwing process.

Mirror plates are another secure method of hanging paintings.

OZ Clips are useful for large works with thin frames, particularly those which are kept in travelling frames.

There is also a range of security screws which can be used when a painting requires protection against theft.

Ideal conditions for the storage and display of paintings

As we have seen, paintings are made up of a number of different materials. Each of these materials has its own particular sensitivity to the surrounding environmental conditions. However, unless you are able to identify the exact materials you will not know their exact sensitivity. To assist museums, galleries and libraries in looking after their collections, guidelines for the ideal storage and display environments have been developed.

Ideally, paintings should be stored in an environment where:

Temperature is constant and moderate—in the range 18–20oC.

If temperatures are generally outside this range in your area, try to ensure that fluctuations are not rapid and are kept to a minimum.

Relative humidity is in the range 45-55%.

This is important for paintings, because most of their components are moisture-sensitive and extremes of relative humidity can lead to physical damage.

Fluctuations in relative humidity should be kept to a minimum and should not be rapid. Fluctuations in relative humidity can lead to severe distortion and to separation of the paint from underlying layers of the painting structure.

Light is kept to the minimum necessary for the activity.

If possible, store paintings in the dark. If light is not required for viewing while the works are being stored, then there is no need for them to be illuminated. This will reduce the risk of fading and discolouration of particularly sensitive components of the painting.

For display it is necessary to have light; but the brightness of the light should be less than 250 lux.

The UV content of the light should be no greater than 75μw/lm and preferably below 30μw/lm.

Steps are taken to protect paintings from dust and pollutants.

For more information

For more information about temperature, relative humidity, light and UV, please see Damage and Decay.

General storage and display guidelines

Careful consideration should be given to the storage site and the storage system. In situations where you are able to achieve the ideal conditions, a good storage system in an appropriate storage site will give added protection to your collection. If the available facilities or the local climate make it difficult for you to achieve the ideal conditions, the selection of the storage site and the maintenance of a good storage system will become even more critical in preventing damage to the collections.

Wherever possible the storage and display sites should be in a central area of the building, where they are buffered from the extremes of climatic fluctuations which can be experienced near external walls or in basements and attics. Basements should also be avoided because of the risk of flooding.

The storage site should not contain any water, drain or steam pipes, particularly at ceiling level. If these pipes were to leak, extensive damage could result.

The storage and display sites should be reasonably well ventilated. This will help reduce the risk of insect and mould infestation.

Inspect and clean storage and display areas regularly. Thorough and regular cleaning and vigilance will also greatly assist in the control of insects and mould.

Do not store paintings in sheds or directly on the floor.

Cover stored paintings with a Tyvek cover. These are easy to make for individual works, using a domestic sewing machine. They will protect the paintings and their frames from dust and insects. These covers will also help to protect the works from fluctuations in environmental conditions.

Always give paintings adequate support and try to reduce the physical stresses which can cause damage.

If you have a number of paintings which are to be stored for considerable periods, consider designing a specific storage area so the paintings can be hung securely for storage. A heavy-gauge wire grid can be used for this purpose. If considering building such a system, consult a conservator for further details.

If paintings are to be stored against walls, ensure that they are placed on padded blocks to take them off the floor level; and ensure that they are not near heavy traffic areas, because they could be damaged as people walk past them or if people drop things on them.

Design your display lighting so that the heat produced by the lights does not affect the paintings.

Heat associated with light can cause localised and differential environmental changes, and subsequent dimensional changes across the painting.

Always avoid direct sunlight on your paintings.

Storing unstretched paintings

Ideally, unstretched paintings should be stored flat. But many larger paintings are too large for flat storage in standard storage furniture. For the full protection of these larger paintings, rolled storage is recommended.

It is important to note that for the flat storage of unstretched paintings, the paintings should be kept on wide, flat shelves or in large flat drawers such as plan chest drawers.

The shelves or drawers should be larger than the paintings. This prevents distortion of the edges of the canvas.

Paintings can be stacked one on top of another, but paintings can be quite heavy and the ones on the bottom have to carry the weight of those on top. So be sure to limit the number of paintings per stack.

Stacked paintings should be interleaved with thin Protecta Foam sandwiched between acid-free tissue.

If possible place the paintings in a large storage box, 100–150mm deep.

When rolling paintings for storage, it is important to note that:

- paintings must be rolled painted side out, otherwise permanent damage which mars the appearance of the work can result;

- paintings should be properly interleaved and the roller properly padded;

- the roller should be as large as possible in diameter—at least 200mm.

Rollers can be specially made of lightweight materials, such as:

- Ribloc, with the ribs on the inside;

- PVC pipe. A 300mm diameter pipe is a good size for most works;

- if you are using a cardboard tube to roll a painting, pad it out to as large a diameter as possible.

Rollers should be covered with a layer of padding- either polyethylene foam such as Plastazote or Dacron wadding covered with clean, white cotton fabric-to compensate for any irregularities in the painting’s thickness.

It is best to roll the painting with an interleaving layer of Tyvek, to prevent any transfer of pigment. The Tyvek should be larger in length and width than the painting. When rolled, the painting should be tied firmly, but not tightly, with cotton tape in several places along the roll.

If more than one painting is to be rolled on a roller, the paintings should be laid out flat and interleaved with Protecta Foam, as for flat storage. Once this is done, the paintings should be rolled onto the roller, all at the same time. Remember, all the paintings should be paint side out.

Summary of conditions for the storage and display

Summary of conditions for storage and display | ||

Storage & Display | ||

Temperature | 18oC–22oC | 18oC–22oC |

Relative Humidity | 45–55%RH | 45–55%RH |

Brightness of the Light | Dark storage preferred, but if light is present it should not be higher than 250 lux. | Should not be higher than 250 lux. |

UV Content of Light | Dark storage is preferred but if light is present, UV content should be and no greater than 75 μW/lm and preferably below 30 μW/lm. | No greater than 75 μW/lm, preferably below 30μW/lm. |

Paintings in Australia\'s climatic zones

Paintings in Australia’s climatic zones |

The climatic zones outlined below are broad categories. Conditions may vary within these categories, depending on the state of repair of your building and whether the building is air conditioned or not. Remember that the variations in environmental condition across Australia are extreme. Therefore, you should be careful if you are transporting paintings from one climatic zone to another—for example, transporting works from a warm moist tropical environment to an air-conditioned gallery. If works are travelling, ensure there is enough time to acclimatise them on their arrival and return. |

Arid |

This climate is generally very dry, however in arid areas it is often very hot during the day and very cold at night. This wide fluctuation in temperature is matched by wide fluctuations in relative humidity, for example from 75%–20% in a day. When caring for paintings in an arid climate it is important to note:

|

Temperate |

A temperate climate is considered a moderate climate, however, temperate climates tend to have a greater range of temperatures than tropical climates and may include extreme climatic variations.

|

Tropical |

These climates are characterised by heavy rainfall, high humidity and high temperatures. When caring for paintings in tropical climates it is important to note that:

|

Keying out

There are a number of problems which can arise when a work is keyed out. For this reason you should never attempt to key out a work unless you have been trained to do this properly by a conservator and you are aware of potential problems.

Older canvases can be extremely brittle and may tear at the corners, or elsewhere along the rollover or tacking edge.

Some paintings which have been distorted over a period of time may have a very strong plastic memory in their canvas or paint layers and keying them out may cause severe stress with cracking and even cleavage and flaking in the stressed areas.

You should carefully consider the strength of the adhesion on mixed-media works such as collage, which may delaminate with movement of the canvas.

What can go wrong with a stretcher and what can you do

As the purpose of the stretcher is to ensure that the canvas is kept taut, it is obvious that a stretcher which can no longer be keyed out is not performing its function properly.

One of the most common reasons for a stretcher to fail is that the keys become damaged-with the protruding end breaking off and the remainder of the key becoming lodged in the keyhole. The removal of the remnants of the key is usually a job for a conservator, because it involves separating the two stretcher members.

In some cases, a stretcher will not remain keyed out and keeps pulling back. If the reason for this is not clear—such as material caught in the key holes—you should consult a conservator.

Sometimes stretchers warp and the temptation is to replace them. If, however, the canvas has taken on the plastic memory of the warped stretcher shape, then replacing the warped member with a straight one may cause more problems than it solves. If in doubt, consult a conservator.

Handling straps

When the work has no frame, handling straps made of synthetic webbing can be screwed onto the backs of frames or stretchers. These materials are available at marine or mountaineering suppliers. Handling straps provide added support for carrying when the frame is too weak or insubstantial to be used for carrying, or when there is no frame, or the work is particularly large and additional support is required.

Labels and inscriptions

The types of labels and inscriptions commonly found on backing boards include framemakers’ labels, chalk marks from auctioneers’ rooms, names and addresses, and other ancillary material. All this material should be noted on the accessioning documentation and the condition report as it can be critical when trying to determine provenance, examine authenticity or simply undertake historical studies.

If you have a problem related to the care, framing or hanging of paintings contact a conservator. Conservators can offer advice and practical solutions.

For further reading

Clifford, T. 1983, The Historical Approach to the Display of Paintings, Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, Vol. 1 (2), Butterworth Scientific Ltd, Guildford, UK, pp 93–106.

Editorial 1987, Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, Frames and Framing in Museums, vol. 4, 1985, pp 115–117; Vol 6, Butterworth Scientific Ltd, Guildford, UK, pp. 227-228.

Hackney, Stephen 1990, ‘Framing for Conservation at the Tate Gallery’, The Conservator, Number 14, The United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, London, pp44–52.

Hasluck, Paul N. 1912, Mounting and Framing Pictures, Cassell and Company Ltd, London.

Keck, Caroline K. 1965 reprinted 1980, A Handbook on the Care of Paintings, American Association for State and Local History, Nashville.

McTaggart, Peter and Ann 1984, Practical Gilding, Mac & Me Ltd, Welwyn, UK.

Payne, John and Chaloupka, Peter, 1986, ‘Framing the 9 x 5s’, Bulletin of the Society of the National Gallery of Victoria, The Society of The National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, pp 11–12.

Seager, Christopher; Hillary, Sarah L.; Weik, Sabine 1986, Art Care. The Care of Art and Museum Collections in New Zealand, Northern Regional Conservation Service, Auckland City Art Gallery, Auckland, N.Z.

National Gallery of Art 1991, Art in Transit: Studies in the Transport of Paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Self-evaluation quiz

Question 1.

The support layer of a painting is:

a) the layer put on the back of the frame to support it;

b) the framework that supports the canvas;

c) the rigid board used to support unstretched paintings when they are being carried; or

d) the layer which carries or supports the image or paint layer.

Question 2.

Which of the following statements are true?

a) Traditionally paintings were produced on stretched canvasses or wooden panels.

b) There is no difference between a stretcher and a strainer.

c) The varnish layer serves only to make the painting look glossy.

d) A stretcher differs from a strainer in that the corners of a stretcher can be keyed out to tighten the canvas.

e) Paintings can be produced on a range of supports.

Question 3.

Fluctuations in relative humidity can damage paintings by:

a) producing dimensional changes in the support, which can lead to separation of the image layer from the support;

b) producing dimensional changes in the support, which can lead to cracking of the paint and varnish layers;

c) warping the stretcher, which in turn produces distortion of the canvas support;

d) increasing the risk of mould attack when the relative humidity is high; or

e) All of the above.

Question 4.

Which of the following statements are false?

When handling paintings you should:

a) Be sure the painting and frame are secure and safe to move.

b) Put your hand around the stretcher bar with your fingers between the stretcher and the canvas. This allows you to get a good grip.

c) Check your route and make sure it is clear. Also make sure all doors are open and that there are people available to assist if you need them.

d) Carry more than one painting at a time.

e) Carry wrapped paintings with extra care, because you cannot see what you are touching.

Question 5.

A good protective framing system will:

a) Protect a painting from knocks, because the frame will take the force of the impact.

b) Include a backing board, to protect the back of the painting from impact damage and to significantly reduce the risk of insect attack and dust build-up.

c) Be designed with protection, the history of the painting and aesthetics all taken into account.

d) Have a slip or a spacer to keep the glazing away from he paint surface.

e) All of the above.

Question 6.

When putting a painting into its frame, you should:

a) Use hammer and nails to fix the painting in place as this is difficult for people to undo and will ensure that it won’t come loose.

b) Ensure that all surfaces contacting the painting eg. the slip, the rebate, the fixings etc are cushioned with an inert cushioning material.

c) Use spacers between the painting and the frame, if the painting fits loosely in the frame.

d) Build up the back of the frame with a stepped profile section to accommodate the backing board, the painting and the glazing and slip, if the frame includes glazing.

Question 7.

Which of the following statements are true?

a) Paintings should be hung securely because they can be badly damaged if they fall off the wall.

b) Paintings should be hung from two points on the wall.

c) The hanging devices should be strong enough to take the weight of the work without becoming stressed or warped.

d) The hanging device should be attached to two points on the frame.

e) If the work is exceptionally heavy, additional support can be given by resting the base of the frame on a shelf.

Question 8.

What are the ideal conditions for storing and displaying paintings?

a) 18-22°C, 55–70% RH, brightness of the light at 550 lux and the UV content of the light no greater than 75μW/lm and preferably below 30μW/lm.

b) 20-30°C, 45–55% RH, brightness of the light at no more than 250 lux and the UV content of the light no greater than 200μW/lm and preferably below 100μW/lm.

c) 18-22°C, 45–55% RH, brightness of the light at no more than 250 lux and the UV content of the light no greater than 75μW/lm and preferably below 30μW/lm.

d) None of the above.

Question 9.

When storing paintings, you should:

a) Ensure that they have adequate support.

b) Place them on padded blocks on the floor, in an area where people are likely to walk past them often so that they can check their condition regularly.

c) Protect them from dust and fluctuations in relative humidity.

d) Roll large, unstretched paintings if you do not have storage furniture which can accommodate them flat.

Answers to self-evaluation quiz

Question 1

Answer: d).

Question 2

Answer: a), d) and e) are true. b) is false. There is a difference between a stretcher and a strainer. A stretcher can be keyed out to tighten the canvas, whereas a strainer cannot. c) is false. The varnish layer protects the paint layer and gives the paint colours a richer appearance.

Question 3.

Answer: e).

Question 4.

Answer: b) and d) are false.

Question 5.

Answer: e).

Question 6.

Answer: b), c) and d) are correct. a) is incorrect. Nails should not be used to fix paintings into a frame, because hammering them in causes vibration which could lead to considerable damage.

Question 7.

Answer: a), b), c), d) and e) are all true.