Objectives

At the end of this chapter you should know:

why people volunteer;

the importance of effective volunteer management;

the importance of a team approach, using volunteers and paid staff;

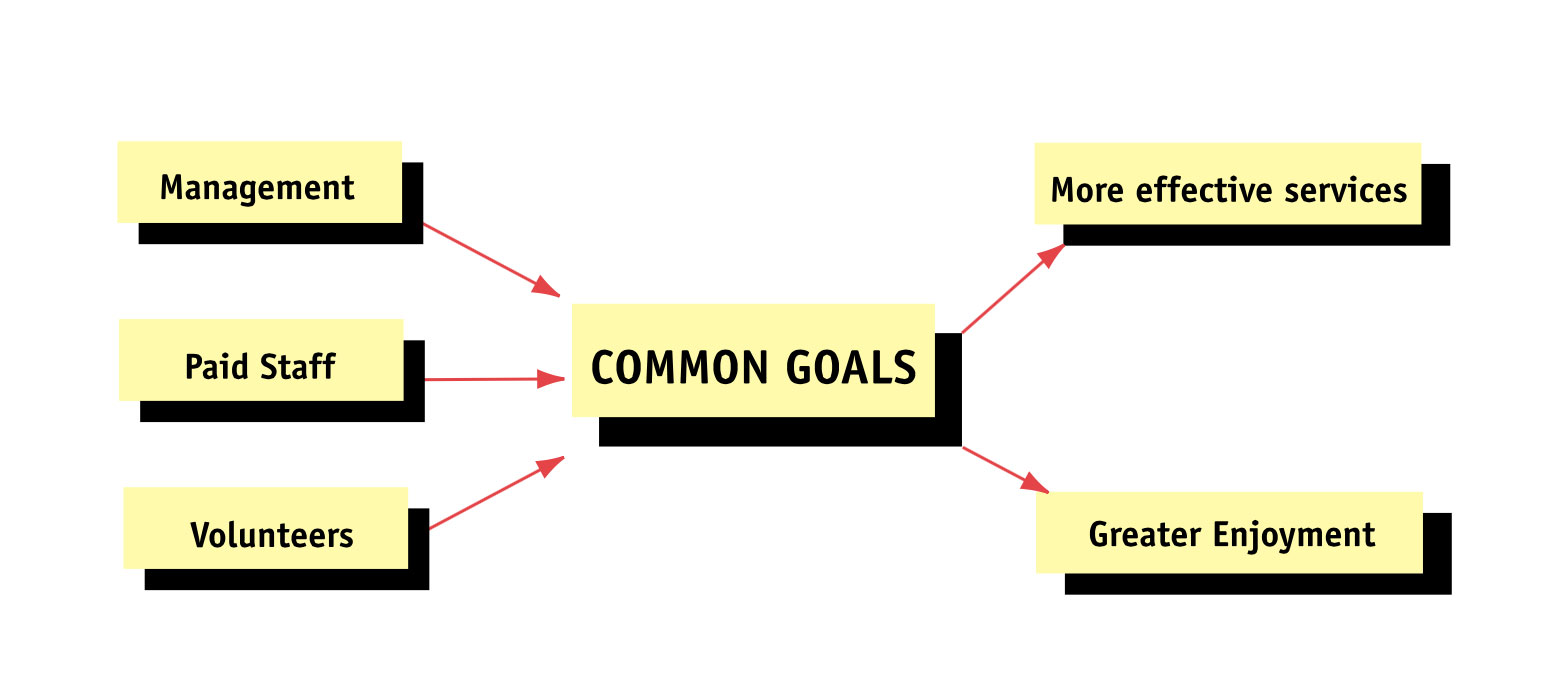

the need for clear, common goals for paid staff and volunteers; and

the potential advantages of having volunteers in your organisation.

Introduction

The assets of cultural organisations are not only the buildings and the collections, but also the people who work in them, both paid staff and volunteers.

In museums, galleries and libraries, volunteers form a significant part of the work force. The volunteer component of organisations varies, from a small number, to the entire staff. Effective management is essential if the full potential of both voluntary and paid staff is to be realised. How this is done will, to an extent, depend on the composition and size of the organisation.

The subject of volunteer management is of crucial importance, whether you are:

- a member of the board or executive;

- a volunteer;

- a volunteer or a paid worker responsible for supervising or managing volunteers; or

- a paid member of staff working alongside volunteers.

- Each of you will have a different but essential contribution to make. Each of you will benefit from:

- targets being achieved;

- a harmonious and productive environment; and

- a stable and contented work force.

Aims of volunteer management

The aims of volunteer management are to:

- recognise and fully utilise the time, skills, experience and commitment of volunteers;

- adopt a management style which is effective, simple and open, and retains spontaneity;

- develop policies and practices based on a good understanding of volunteering and related issues;

- encourage cooperative working relationships that facilitate mutual trust and enjoyment between volunteers, paid staff and management; and

- ensure achievements match the agreed targets of the organisation.

Definition of volunteering

While definitions vary slightly, any definition needs to contain three essential elements. Volunteering is done by choice, without monetary reward, and for the benefit of the community.

Without monetary reward does not exclude the payment of out-of-pocket expenses, which are a reimbursement for actual costs incurred rather than a reward.

Roles, involvement and profile of volunteers

Volunteers working within museums, art galleries and libraries perform a huge range of duties, including:

- policy formation and management, for example, serving on boards and committees;

- practical tasks—renovating buildings or artefacts, arranging displays, collecting items of historic interest;

- interaction with the public—reception, guides, public speaking;

- administration—cataloguing, recording, bookkeeping;

- publications—newsletters; and

- fundraising—special events, trading tables.

In country areas and in small metropolitan organisations, the majority of workers is likely to be volunteers. The extent to which large city museums, galleries and libraries involve volunteers varies from place to place, although the majority of staff are likely to be paid workers. Both large and small organisations frequently include volunteers on their boards and committees.

While no definitive across-the-board survey has been conducted, indications are that many of the volunteers are women in the older age-bracket. However, this profile does appear to be changing, with more men and young people becoming involved.

Attitudes to volunteering

Volunteering is, of course, not new. What is new is:

increased attention to the concept and practice of volunteering;

recognition of the contribution of volunteers;

acknowledgment of the advantages of developing joint partnerships between paid and voluntary workers;

the fact that volunteers are generally more selective about where they volunteer and what they do, so that their own interests are being met while doing something worthwhile;

an acceptance of the fact that effective management is essential if the knowledge, skills and experience of volunteers are to be put to the best use; and

some museums and galleries do not discriminate between paid and non-paid staff and refer to all staff as workers.

Benefits of volunteer involvement

Volunteer involvement benefits an organisation as it:

encourages community participation;

initiates, enhances and extends services; and

provides a cost-effective service.

Benefits for the individual volunteer include opportunities to:

get with the action and become involved in new areas;

advocate change and seek more say in decisions;

improve and extend services;

pursue a long-term or new interest;

maintain existing skills or develop new skills; and

increase social contacts.

Effective volunteer management brings benefit to:

the project;

the organisation, including the paid workers;

the volunteer; and

the community at large.

Dangers of volunteer involvement

Whatever the activity, exploitation can occur. Volunteers can be exploited if:

they are allocated inappropriate tasks;

they are allocated a task which is not done of one’s own free will—an occurrence in some organisations;

the program is inadequately planned or poorly managed and resourced; and

attention to the task at hand is so rigid that volunteers are prevented from putting forward their own ideas.

Paid workers can be exploited if:

they are expected to work alongside, and perhaps supervise, volunteers without account being taken of the additional time and skills involved; and

they are replaced by volunteers to save money when, in fact, the job requires the services of paid workers.

When funding sources are cut, both paid staff and volunteers are faced with the dilemma of deciding which is the best way forward. Not only are paid workers in danger of losing their jobs, volunteers may be expected to perform tasks and roles which they do not choose to do and which have been deemed to be the province of paid workers.

The risk of conflict between paid and voluntary workers increases when volunteers are thought of as angels and paid workers are thought of as interested only in the wage package.

Costs of volunteer involvement

Volunteer involvement is not free. Direct monetary costs to the organisation include:

reimbursement of volunteers’ out-of-pocket expenses;

public liability and personal accident insurance;

supervision and/or management by paid staff;

training costs;

facilities; and

miscellaneous costs, for example, newsletters, catering for special events.

Direct monetary costs for the volunteer include:

travel to and from the work-site; and

expenses incurred in the conduct of the job.

While not all volunteers will wish to claim out-of- pocket expenses, some people are precluded from volunteering if reimbursement is not offered.

Prerequisites for success

- Identify your goals, that is, what you want to achieve.

- Think through how these goals can be achieved.

- Develop policies to guide practice.

- Examine the situation as it stands at present.

- Establish structures which ensure the flow of information and enhance decision-making.

- Institute strategies and establish who is responsible for what, to be done by whom, and when.

Identify your goals

Whether you are considering your organisation as a whole or just a project within it, everyone involved will want to know where they are heading, that is, what outcomes you are all hoping to achieve from your efforts.

These outcomes can sometimes be measured quantitatively, for example, 1,000 visitors viewed the exhibition; or qualitatively: visitors were spread across all ages and ethnic groupings.

The clearer your goals, the easier it is to plan and review progress. Any proper review or evaluation is possible only when results can be placed alongside goals.

Of course goals can change as your ideas, experiences and situations change, so a regular review of goals keeps an organisation on track.

Develop policies to guide practice

Whether your organisation is large or small, staffed by a combination of paid and voluntary staff or entirely by volunteers, development of a policy document will clarify the ground rules. These ground rules will guide your practice.

The policy document could include why volunteer involvement is welcomed, for example, to involve the community, to enhance or extend services; and a commitment to:

- providing volunteers with a clear idea of their duties;

- ensuring volunteers are given the necessary facilities, orientation and training to enable them to perform their duties adequately;

- developing a team approach, with all volunteer and paid staff aware of each other’s particular contribution;

- providing reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses, insurance cover, and safe working conditions;

- providing opportunities for information exchange and involvement in decision-making processes and review;

- providing adequate support and supervision; and

- identifying the person responsible for coordinating or managing the volunteers.

Understand the work environment

It is necessary to have a clear understanding of:

- the fact that effective volunteering is a reciprocal arrangement, with the volunteer both giving and receiving;

- available resources; facilities and funds;

- staff, both voluntary and paid—numbers, attitudes, skills, attributes and availability;

- political factors;

the need for accountability; and - the community served by the organisation, for example, its make-up, interest in your project, attitudes to volunteering.

Organisational structures

Structures should incorporate:

- the provision of relevant, up-to-date information and the opportunity for feedback and review;

- mutual knowledge and respect for the different roles undertaken by various staff members;

- a close relationship between management and the staff team;

- involvement in decision-making processes that affect the volunteer’s job and work environment;

- acceptance that everyone, management and staff, paid and voluntary, is working toward a common, overall goal; and

- integration of paid workers and volunteers into the one staff team.

Strategies

Planning strategies will be much easier once:

- goals have been identified;

- volunteer policies are in place;

- the environment within which the organisation operates is clear; and

- structures that facilitate communication have been established.

Strategies are needed for:

- recruitment and selection;

- orientation;

- training—initial and ongoing;

- team approach; and

- supervision, support and review.

Recruitment and selection

Before recruitment begins, thought should be given to the profile of the volunteer team. Are you seeking a cross-section of ages and backgrounds, and both male and female volunteers, so that the team is representative of the general community; or is this immaterial?

Clear job descriptions must be in place before recruitment begins. Each job description should include the overall job as well as detailed tasks, for example, a receptionist who will greet visitors, answer queries made personally and by phone, and operate the word processor. The person to whom the volunteer will be responsible should also be named.

Thought should also be given to:

- required skills, current or to be acquired;

- personal attributes; and

- time commitments.

Potential volunteers should be informed of:

- the organisation’s expectations of them, for example, attendance at a training course for museum guides; and

- what the volunteer can expect from the organisation, for example, out-of-pocket expenses and insurance cover.

As in the case of paid staff, haphazard selection will assist neither the organisation nor the person recruited.

Successful selection involves matching both:

- the volunteer’s skills, attributes and time availability with the job description; and

- the needs and expectations of the volunteer with the needs and expectations of the organisation.

Orientation

If recruitment and selection procedures have been well devised, orientation will have begun before the volunteers begin work. New volunteer staff will know and accept the purpose of the organisation and the job expected of them. After recruitment, they will want further details about the organisation: about the management and service personnel, organisational structures and further details of their particular job.

Areas which could be included during orientation are:

- introductory reading material about the organisation;

- a tour of the organisation, its services, programs and facilities;

- an introduction to staff—paid and voluntary;

- personnel matters;

- the organisation’s systems of operation, including communication channels;

- details of the job for which the volunteer has been recruited; and

- occupational health and safety, and evacuation procedures.

A staff handbook can facilitate the orientation process. If the handbook covers the needs of both paid and voluntary staff, then a team approach is encouraged from the outset.

Training

While orientation to the organisation and the job is a must for all volunteers, training will depend on the job to be done and the current level of knowledge and skills of the volunteer. Often volunteers are recruited because they already have the experience and skills to do the job: a retired shipwright could take on the job of refurbishing a sailing vessel, for example. On the other hand, volunteers may not have the necessary skills.

The important thing for both the organisation and the volunteer is to ensure volunteers are prepared, so that they can adequately perform their work.

Remember that there are many ways of learning and of training people. Look to options such as a buddy system, mentoring, modelling good practice, and guided reading.

Further training may be necessary if the volunteer wishes to take on additional or different jobs, or the organisation introduces a new program.

A team approach

Good teamwork and a feeling of mutual trust and respect rely on:

a firm commitment by management and paid staff to volunteer involvement;

particular roles, expectations and responsibilities of all parties being clearly defined;

recognition and appreciation of each other’s different but valuable contributions;

a willingness to accept and work within the advantages and constraints posed by volunteer involvement; and

all parties seeing themselves as working toward a common goal.

The understanding, approval and involvement of paid staff at all levels is crucial to effective teamwork. If this is missing, further consultation and discussion will be necessary. Any problems must be dealt with as they arise, and appropriate action taken.

Teams are built as volunteer and paid staff work together from the planning stage through to the review of achievements.

Supervision, support and review

Supervision, support and review strategies are as necessary for volunteers as they are for paid staff.

Provision must be made for the dissemination of adequate information, an appropriate place in which to work, necessary equipment, and the establishment of clear communication channels and supervision between those doing the work and the person ultimately responsible.

Support does not preclude constructive advice or criticism. At times and in certain circumstances, constructive criticism may be the most valuable form of support.

Regular reviews of how individual volunteers, and the staff as a whole, are feeling and operating are a must. They will provide the opportunity for the necessary adjustments to ensure satisfaction with job performance and a happy and dynamic team.

Other entitlements

Volunteers do not expect a monetary reward for their efforts but, in addition to an enjoyable and worthwhile experience, they do expect:

recognition of, and feedback about, their performance;

satisfactory and safe working conditions;

the right to claim out-of-pocket expenses; and

public liability and personal accident insurance cover.

If the organisation has decided not to offer out-of- pocket expenses, or not to take out insurance cover, volunteers should be made aware of these facts before they begin work.

Resources to tap

Over the last few years, every state and territory in Australia has established a state/territory volunteer centre. Regional centres have also been established in some country areas.

Ring the centre closest to you for advice or information about:

training opportunities—one option is a nationally accredited course in volunteer management, available both on-site and through distance learning;

conferences; and

publications—books, newsletters, videotapes, the Australian Journal on Volunteering, the Australian Bureau of Statistic’s surveys on volunteering.

Information and assistance is at hand. Please use it!

Australian Volunteer Centres

Volunteer Centre of SA Inc.

1st Floor, 155 Pirie Street

Adelaide SA 5000

Phone (08) 8232 0199, Fax (08) 8232 5161

ACT Volunteer Association Inc.

30 Storey Street

Curtin ACT 2605

Phone (02) 6281 6669, Fax (02) 6282 2200

Northern Territory Council for Volunteering Inc.

Shop 1, 1st Floor Paspalis Centrepoint Smith Street Mall, Darwin

PO Box 36531, Winnellie NT 0821

Phone (08) 8981 3405, Fax (08) 8941 0279

Volunteer Centre of New South Wales Inc.

2nd Floor, 105 Pitt Street

Sydney NSW 2000

Phone (02) 9231 4000, Fax (02) 9221 1596

Volunteer Centre of Queensland Inc.

Room 415, 4th Floor Renney’s Building

155 Adelaide Street

Brisbane QLD 4000

GPO Box 623, Brisbane QLD 4001

Phone (07) 3229 9700, Fax (07) 3229 2392

Volunteer Centre of Tasmania Inc.

167 Campbell Street

Hobart TAS 7000

Phone (03) 6231 5550, Fax (03) 6234 4113

Volunteer Centre of Victoria Inc.

2nd Floor Ross House

247-251 Flinders Lane

Melbourne VIC 3000

Phone (03) 9650 5541, Fax (03) 9650 4175

Volunteer Centre of Western Australia Inc.

79 Stirling Street

Perth WA 6000

Phone (08) 9220 0676, Fax (08) 9220 0617 or 9220 0625

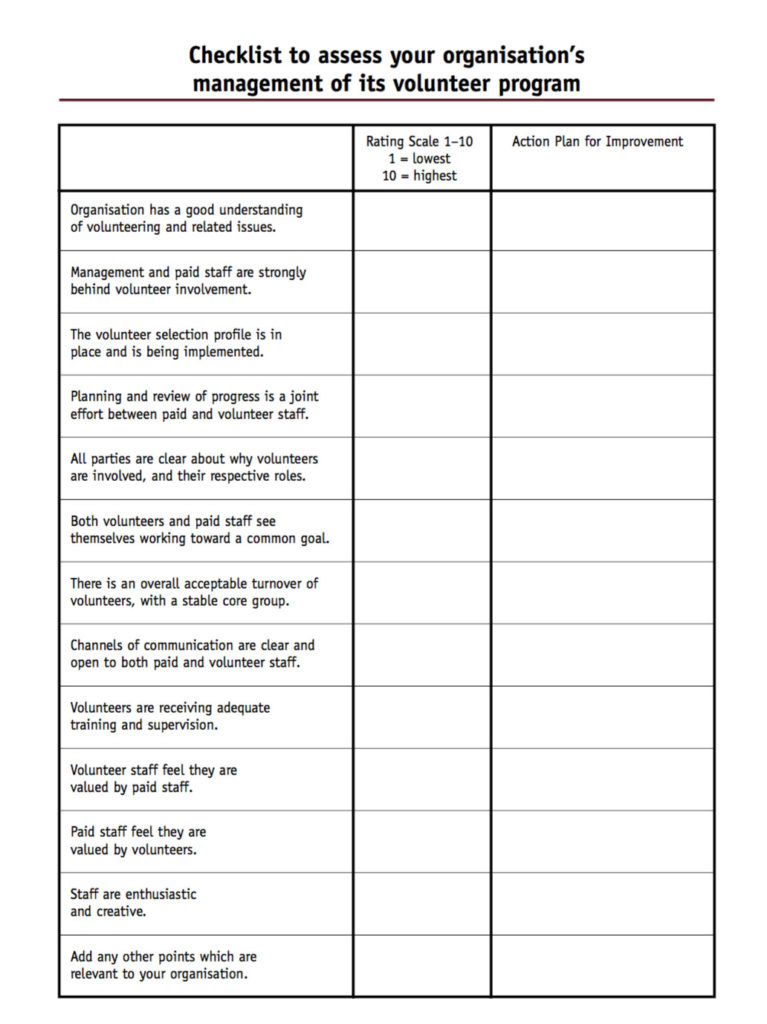

Checklist to assess your organisation\'s management of its volunteer program

Volunteer Centre of Queensland Inc.

Room 415, 4th Floor Renney’s Building

155 Adelaide Street

Brisbane QLD 4000

GPO Box 623, Brisbane QLD 4001

Phone (07) 3229 9700, Fax (07) 3229 2392

Volunteer Centre of Tasmania Inc.

167 Campbell Street

Hobart TAS 7000

Phone (03) 6231 5550, Fax (03) 6234 4113

Volunteer Centre of Victoria Inc.

2nd Floor Ross House

247-251 Flinders Lane

Melbourne VIC 3000

Phone (03) 9650 5541, Fax (03) 9650 4175

Volunteer Centre of Western Australia Inc.

79 Stirling Street

Perth WA 6000

Phone (08) 9220 0676, Fax (08) 9220 0617 or 9220 0625

In conclusion

Volunteers represent a huge human resource, which in the past has been largely hidden and undervalued. This situation is now changing. Along with the increased recognition of volunteers, the importance of effective management is also being acknowledged.

Effective management is the key to ensuring that the time, skills, experience and commitment of volunteers are put to the best possible use, that organisational goals are achieved and that everyone enjoys the experience.

Meeting this challenge requires a joint effort by:

the management of the organisation;

the person appointed to manage or coordinate the volunteers;

paid staff who work alongside the volunteers; and

the volunteers themselves.

If you have a problem relating to adequate skills in conservation, contact a conservator. Conservators can offer advice and practical solutions.

For further reading

Kupke, Diana, 1991, Volunteering: how to run a successful volunteer program with happy volunteers and how to get more satisfaction out of being a volunteer, Elepahs Books, Perth.

Millar, Sue, 1991, Volunteers in museums and heritage organisations: policy, planning, and management, Office of Arts and Libraries, London.

Noble, Joy and Rogers, Louise, 1998, Volunteer Management: An Essential Guide, Volunteering South Australia, Adelaide.

Self-evaluation quiz

Question 1.

Should every person who seeks a voluntary job be accepted?

Question 2.

Name three strategies which will help meld long- serving volunteers with new recruits, and volunteers with paid staff.

Question 3.

In order to be successful, does every volunteer program have to be managed in exactly the same way?

Answers to self-evaluation quiz

Question 1.

Answer: No. If both the organisation and the volunteer are to benefit, then a double match is necessary. An inappropriate match is a liability to the organisation and is likely to destroy the volunteer’s enthusiasm. It may be possible to refer the potential volunteer to an area more in keeping with his or her skills or interests. If the person is obviously not ready to volunteer, for example, recovering from trauma or illness, referral to a social or support service may be appropriate.

Question 2.

Answer: Possible strategies include:

involving a volunteer and paid staff in the planning, recruitment and selection of new volunteers and in the orientation process;

asking a long-serving volunteer to buddy a new volunteer for the first few months;

when reviewing progress, involving the whole staff team;

seeking perspectives and suggestions from long standing and new volunteers as well as paid staff.

Question 3.

Answer: No. The size of the organisation, its function, the make-up of staff—paid and voluntary or entirely voluntary—its location and geographical spread will all have an influence on the manner in which the program is managed. However, every program needs to establish its goals, as well as structures and strategies, to achieve those goals.